I put my journal behind a paywall, so why am I talking to you about Open Access?

It is easy to forget who does what in the world of publishing, so I begin by refreshing the minds of older readers, and informing younger ones. I will take the process of submission, peer-review and editing as understood. Although I dismiss it quickly here, this is really the crux of the work involved in science, and what follows is simply the recording of this process.

Academics are not (usually) superstars, nor looking for enormous numbers of readers, but there would be little point to recording our work if we had no readers, or if our work were inaccessible, and so publishing is a necessity. However, we have got into a state in which much of our work is behind a pay wall, and thus inaccessible to most. Whether or not we need our work to look pretty and appealing speaks more to our readers as humans than academics. Perhaps it goes without saying that an audience is likely to be larger the more appealing the presentation, and that’s not just the writing style but the layout and presentation of the text itself. And this is not new.

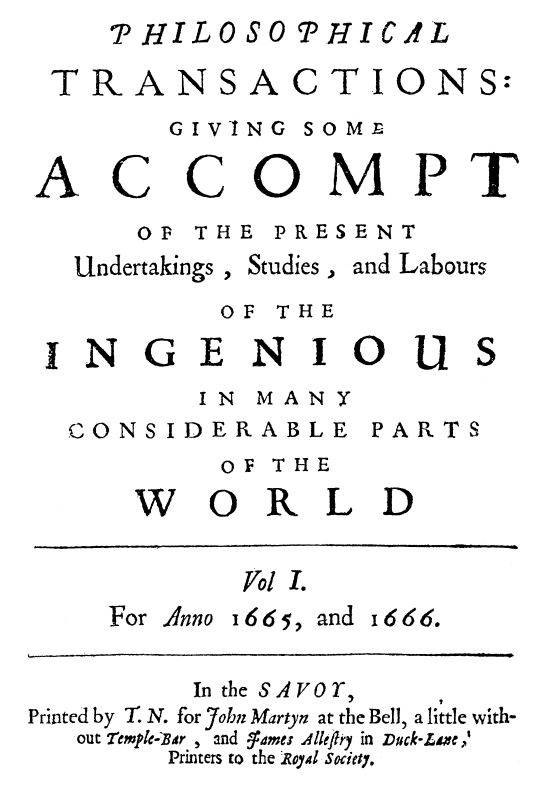

Right back to the first scientific journal, Philosophical Transactions in 1665, it is clear that the papers were type set and presented in the manor of a book, perhaps analogous to a collection of short stories. At the start, these were reports of studies that were presented at meetings. Producing proceedings of learned societies became the way in which most scientific journals began. Only later did it become possible to submit a manuscript that had not been presented. And later still when publishers began to manufacture their own scholarly journals in the absence of any academic society.

Being the editor of a society journal means being elected by members of that society, and being responsible to an editorial board, normally made up of the society’s members. Until very recently, and I’m thinking back to my first interactions with editors for my first few publications, submitting to the journal meant producing three (or sometimes more) double spaced copies of a manuscript and mailing them to the editor. Editors of bigger journals had secretaries dedicated to handling the administration of the paper. Following a telephonic enquiry, the copies were sent out to referees by post and sent back to the editorial office with a typed report often together with the marked up manuscript. Once the editor had received all reports, they communicated their decision back to the corresponding author (i.e. the one to whom correspondence was addressed) and, once accepted, the article went into production. Prior to personal computers being commonplace (only 25 years ago), each journal would have had to have had a publisher to set the type and print the pages. Clearly, this was beyond the scope of individual societies and the publisher was a necessity. Libraries had to pay for copies of journals, as the cost of publishing had to be offset by the society.

The advent of desktop publishing changed the need for publishers and brought many small society journals onto a larger platform where they could produce attractive content (over the typewritten documents that had been stencil duplicated or similar) and sent around to members. However, for small societies there was no professionalism involved as it devolved to the editor to publish society material. This is where I entered the stage in 2009 when I took over as editor of the African Journal of Herpetology. Thankfully, email had taken the place of the postal service, but once a manuscript was accepted I was the one who needed to type-set the documents (in Quark) and send out proofs to authors. Once proofs were corrected and the issue was ready, I had to find quotes from 3 printers, deliver discs and ultimately collect boxes of printed journals. Back at home, I also packed all of the copies into labelled envelopes (with some help from friends) and carried the boxes once again to the post office.

After the first issue, I realised that I could not do all of this work indefinitely. I knew that there were publishers who were interested in acquiring the journal into their stable, and I contacted them and started negotiations. In 2011, the first copy of AJH from a professional publisher emerged, and allowed me to go back to editing the content through peer review.

At the time, I was aware of Open Access and considered this as an option for the journal. Open Access would have required that someone pay for the type setting, and the society would still have to pay for an online dissemination platform, given that they did not have their own platform. This would have meant that authors paid for getting their manuscripts into print. And then, like today, the decision was that our authors would not be willing to pay. Other, richer, societies were able to go Open Access with the costs being covered by their members. For one, Salamandra, this became an incredibly successful model, with submissions increasing as well as their Impact Factor. But it did become too much, and eventually a charge is now levied to the authors (albeit small). However, they (and other societies) demonstrate that Open Access is possible on an independent platform.

Why don’t all society journals do without publishers, and go Open Access independently?

The first problem is that societies generate income from journals. Subscribers to print or virtual copies pay the society, and this can defray a large part of the cost of publishing otherwise carried the members. Going Open Access means losing this revenue, as well as taking on the extra costs.

The second problem for many societies is that their members are paying, and the councils or committee’s elected to represent the members do not feel that it is fair for their members to pay for open access for everyone else. Part of the privilege of being a member of the society is having a free (or more accurately paid through membership) copy of the society’s journals. The costs are not high, and the exclusivity of members having Open Access while it is denied to others is perhaps just a hang over from the days when the only other copies were in the library. Certainly, the costs are nothing like those which authors are now charged by publishers to turn their accepted manuscripts Open Access.

In my opinion, the current situation is truly crazy. Tax-payers (in the main) pay for science to be conducted at universities and other institutes. In places where Open Access is mandatory, the tax-payer pays again to have the research published at a cost that is far inflated from the actual production costs. Publishers are getting fat, and the losers are the scientists (whose funding is reduced to pay publication costs) and the tax-payers who end up feeding the greedy publishers.

What will it take to break the vicious cycle?

We need new models for publishing. Society journals are still kings in this game and ultimately hold the cards for moving away from filling the pockets of publishing companies. What we have seen in recent years is that journals can come from nowhere to become dominant players in the system. Think PLoS ONE, and the even more recent Scientific Reports. These mega Open Access journals didn’t exist 10 years ago. And they don’t need to exist 10 years from now. What is needed is for governments to fund societies for the actual costs of publishing their own content. This could cover type-setting and the additional IT infrastructure (on-line submission system and online dissemination platform). Most (if not all) societies are not-for-profit organisations, and only need to cover the costs of publishing.

Why would a government in one country pay for the costs of researchers from another publishing in their sponsored journal?

Soft power. It is not in the interests of governments to have any scientific content behind a pay wall. The relatively small costs of grants to societies, together with some simple accounting for papers published, would be tiny compared to the current costs that many are handing over to publishers. Have your country’s logo stamped all over the pages if you must, but it really wouldn’t cost what you are currently paying. Think of the soft power involved in diseminating peer reviewed independent science.

Clearly, scientists in some countries might be worried about handing their publications to their government to disseminate. For this reason, perhaps governments might not be the correct long-term solution for many scoiety journals. Instead, there is potential to obtain grants from philanthropic societies: The Open Society Foundations might be one such source.

But wouldn’t that put all editors back in the position that I desperately wanted to get out of in 2009?

Yes, clearly there needs to be a not-for-profit clearing house that societies can use to pass on their manuscripts. Such places exist. Most governments have their own governmental publishers. Although it would be understood that academic freedom might fly in the face of some governments being held responsible for publishing content. Many countries have institutes with publishing wings. We could even use commercial publishing houses, if we could only curb their greediness.

Alternatively, we could get more savvy as authors and start using La-Tex software to compose or at least submit manuscripts. Most of us have become too dependent on word processors, and we could step up to submitting in La-Tex. Submission software could allow us to cut and paste our content into La-Tex editors online. It’s all possible. I think that many academics would be happy to submit via La-Tex if this meant that their content went Open Access.

Can we afford not to change?

If you are from a rich country or institution, then you can probably afford the current system. Those who cannot are researchers in disadvantaged countries. In some cases, the cost of publishing Open Access is greater than the cost of the research. These are insurmountable costs for many researchers. We have a massive hole in scientific contributions from the poorest of nations, and the current Open Access models will see their work being the most hidden from view, while the countries paying for their work do so disproportionately. But even developing countries could be winners in a new Open Access model. By sourcing the relevant IT skills in country, governments of middle-income countries could facilitate the content of their own society’s with relative comfort. In my opinion, everyone should publish work from scientists in the poorest countries as Open Access without any charges.

What is needed for this change?

- Societies need money. Editors can’t be publishers.

- We need free software. We desperately need good, free editorial management software. There are some free versions out there, but what we need are free versions that are at least as good, if not better, than existing platforms (e.g. ScholarOne; Editorial Manager).

- We need a free La-Tex interface with robust templates for all societal journals. Ideally, this would be packaged with the above editorial management software. This must have the ability to cope with figures and equations, and the unusual demands that some society journals have.

- We need a solution for hosting and disseminating the Open Access society journals (and their supplementary information if not hosted elsewhere) in perpetuity. This last point is perhaps the most expensive, and almost certainly requires government assistance. Maybe this is an interesting use of the block-chain with libraries keeping the data. It would be an interesting way to build a doi with editor and referee unique IDs, and the document's information hanging off.

- We need to take back our content stuck behind pay walls. Yes, it’s time for you to all to dig up those old submitted manuscripts and submit them to an institutional repository where it can be accessed for free.