Doing a PhD is stressful and you'll need a support network

Stress is a natural part of life and many people are at their most productive when they are under pressure. This would most typically be a deadline. Although deadlines don’t work for everyone. Douglas Adams famously claimed to “...love the whooshing noise they make as they go by.” Problems arise when we become unable to fully respond. In the academic environment, pressures and expectations can elicit unpredictable survival responses as if you were surviving an attack and prompting you to fight, flight or freeze. Additional demands on your time may also push your life off balance, so that you start to neglect your personal relationships, exercise regime or even nutrition and personal hygiene. There is also the high likelihood that you will suffer feelings of inadequacy due to imposter syndrome (see here).

Doing a PhD will be the cause of stress not only in your working life, but will also impact other areas of your life. Being aware of this at the outset will allow you to alert close members of your non-working life (think partner, family and friends) that they may well need to act as a support network. It is worth tracking your mental health during your PhD to check that you are not getting into difficulties. See part 5 to a guide on how to track your mental health.

Although there are not many studies on mental health for PhD students, those that exist (as well as surveys: Nature 2019) all suggest that there is a significant toll, which is proportionately higher than others in society (Levecque et al 2017). Whatever your prior experience of stress in a working environment, academia is known to be particularly stressful, and as a PhD student you are likely to absorb a significant amount of this stress into your own life (Strubb et al 2011).

The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) is a simple instrument used to measure occupational health. Because it is simple to score, you can perform it on yourself at any time during your PhD studies, and you can use your responses as an indication of whether you need to reach out to occupational or professional support networks.

Right now, I suggest that you read through the questions in the GHQ and record your answers as a baseline. Keep the scores somewhere safe. During the course of your PhD, if you feel that your scores may have changed take the test again and compare them with your saved scores. Although there are no hard rules, if three or more of your scores have moved by two or more points then you need to discuss this with your support network and decide whether or not to seek professional help.

|

General Health Questionnaire: Have you recently... |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

been feeling reasonably happy, all things considered? |

Better than usual |

Same as usual |

Less than usual |

Much less than usual |

|

lost much sleep over worry? |

Not at all |

No more than usual |

More than usual |

Much more than usual |

|

been feeling unhappy and depressed? |

Not at all |

No more than usual |

More than usual |

Much more than usual |

|

felt you couldn’t overcome your difficulties? |

Not at all |

No more than usual |

More than usual |

Much more than usual |

|

felt under constant strain? |

Not at all |

No more than usual |

More than usual |

Much more than usual |

|

felt capable of making decisions about things? |

Better than usual |

Same as usual |

Less than usual |

Much less than usual |

|

been able to face up to your problems? |

Better than usual |

Same as usual |

Less than usual |

Much less than usual |

|

been thinking of yourself as a worthless person? |

Not at all |

No more than usual |

More than usual |

Much more than usual |

|

been losing confidence in yourself? |

Not at all |

No more than usual |

More than usual |

Much more than usual |

|

been able to enjoy your normal day-to-day activities? |

Better than usual |

Same as usual |

Less than usual |

Much less than usual |

|

been able to concentrate on whatever you are doing? |

Better than usual |

Same as usual |

Less than usual |

Much less than usual |

|

felt that you are playing a useful part in things? |

Better than usual |

Same as usual |

Less than usual |

Much less than usual |

Even if you don’t feel that you need the support of your institution now, it is worth finding out how they can support your mental health. Although there has been some stigma attached to difficulties with mental health in the past, most institutions accept that pressures are mounting on postgraduate students and that they require support. They may well have experienced councilors for you to consult with. Importantly, you should realise that none of these symptoms is unusual and that there is a high chance that many of your colleagues are also feeling symptoms. Knowing that your problems are shared and reaching out to support networks is an excellent way to prevent them from escalating beyond your control.

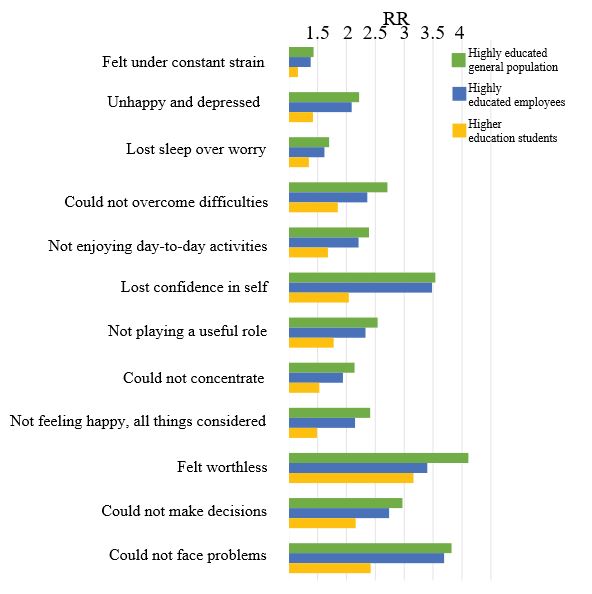

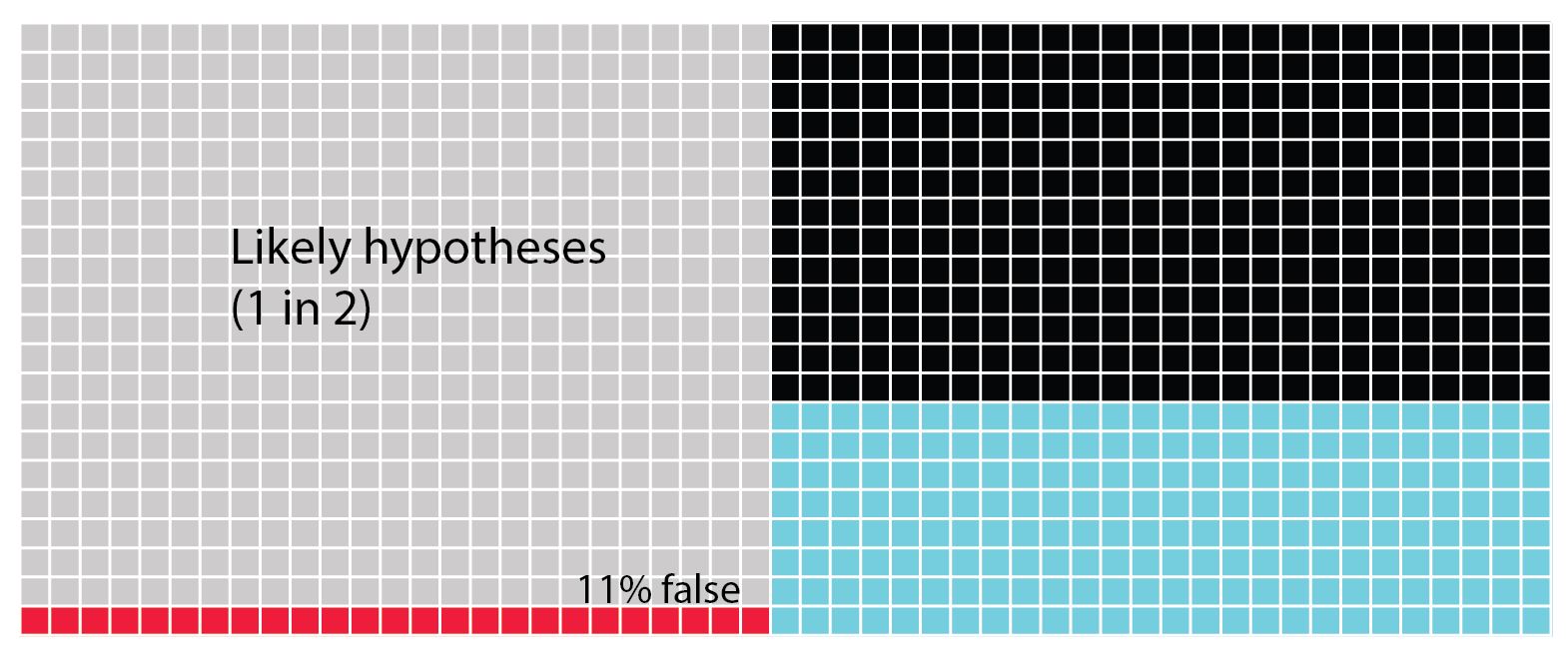

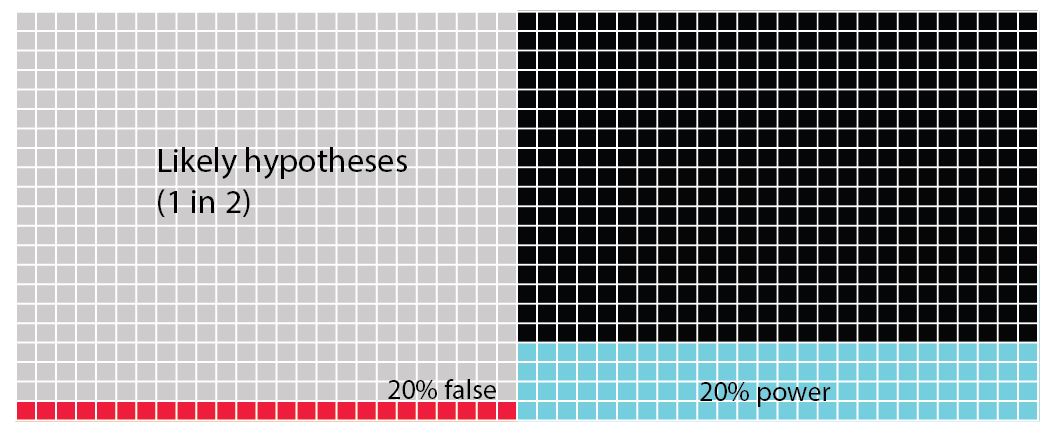

A study into the mental health of PhD students in Belgium exemplifies the kinds of difficulties that they face when compared with other similar groups (Levecque et al 2017).

A comparison of the mental health of PhD students (data from Levecque et al 2017) with highly educated general population, highly educated employees and higher education students using the General Health Questionnaire. The Risk Ratio (RR: adjusted for age and gender) in PhD students in Flanders, Belgium is consistently higher (>1) when compared to any of the other surveyed groups.

No matter how you think of your own abilities to cope with mental health issues, doing a PhD will cause you additional stress and provoke your coping mechanisms into play. Additional stress could all be entirely beneficial, and could find yourself learning how stress affects your personality towards these positive outcomes. On the other hand, you may find that additional stress unexpectedly affects your personality, and that this will impact on both your home and working relationships. Some people will find that the additional stress will manifest itself in physical symptoms that need medical treatment. Moreover, as academia is a particularly stressful environment, you will likely take on some of this environmental stress in addition to any stress associated with your studies. Additional stressors come from home and family situations. Your best means of coping will be to have a support network in place and to understand where and with whom you can discuss any concerns. Knowing who this is and how and when to approach them will put you in a stronger position if you need them in future.

References

Levecque, K., Anseel, F., De Beuckelaer, A., Van der Heyden, J. and Gisle, L., 2017. Work organization and mental health problems in PhD students. Research Policy, 46(4), 868-879.

Stubb, J., Pyhältö, K. and Lonka, K., 2011. Balancing between inspiration and exhaustion: PhD students' experienced socio-psychological well-being. Studies in Continuing Education, 33(1), 33-50.