Visiting the Chinese Academy of Sciences - Kunming Zoological Institute

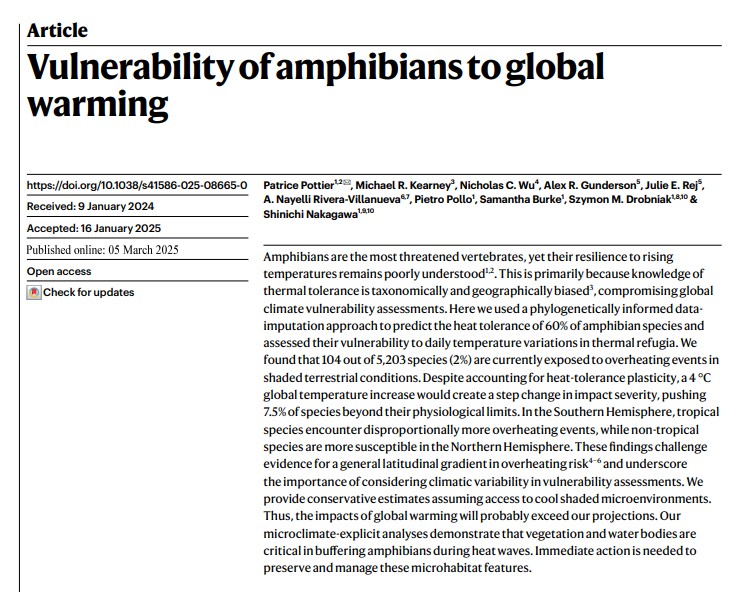

The Chinese Academy of Sciences hosts many of the premiere research institutions in China, including the Kunming Zoological Institute which shares its grounds with the Kunming Botanical Institute, a few kilometers north of downtown Kunming. I was very interested in meeting Che Jing and her research group, who have received international acclaim for their groundbreaking work on amphibians. In turn, they invited me to visit KZI and give a talk.

It was a great pleasure to meet so many keen and enthusiastic early career resaerchers, and all interested in amphibians. It was a special pleasure to meet Alex Karuno, originally from the Kenyan National Museum in Nairobi. Alex studied with Patrick Malonza before he moved to China to continue his PhD studies. You can find Patrick's name at the top of a list on my CV page.

Alex should finish his PhD by the end of this year, and we wish him all the best for doing that!