Laurie becomes Dr. Araspin

Those of you who follow this blog will be very familiar with Laurie Araspin as she has been the subject of lots of posts over the years (for example, see here, here and here).

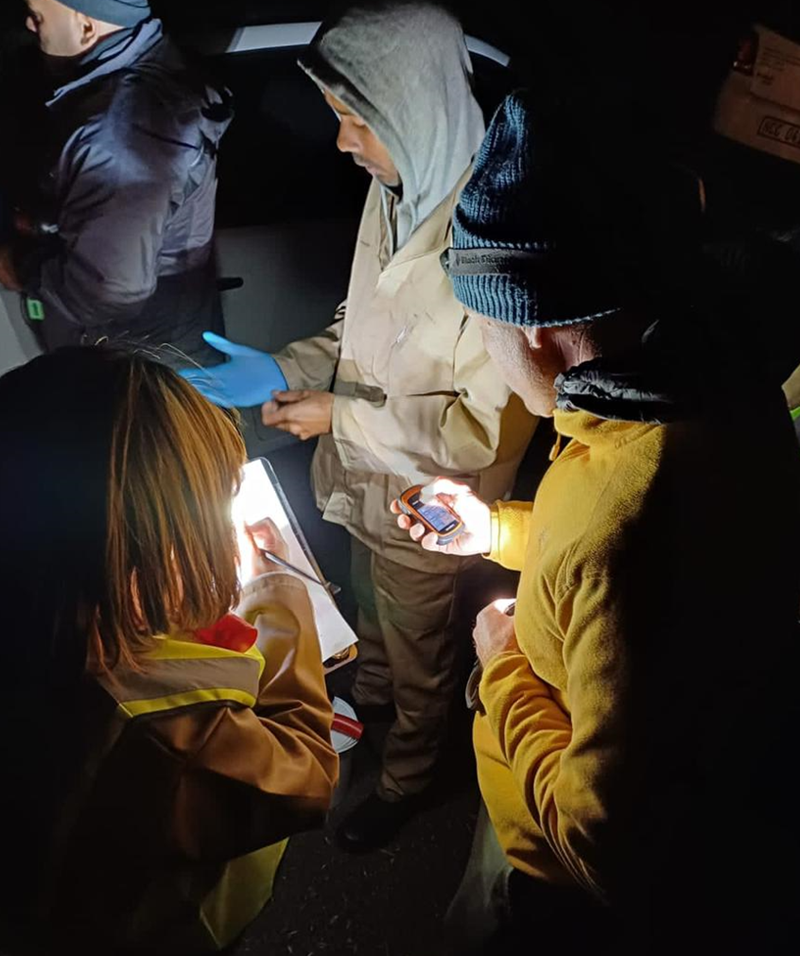

It was a rainy day in Paris and the gig didn't start well with all the normal IT problems associated with trying to marry a live event with an online audience, but Laurie braved it out and presented her thesis work to a packed auditorium.

Finally, after the presentation was done, the jury deliberated and pronounced Laurie to be Dr. Araspin. And then the party began.

The jury consisted of some familiar faces to MeaseyLab members past and present.

Bottom right, Carlos Navas (on screen from Sao Paulo or perhaps on sabbatical in the USA) is having his audio checked by Anthony Herrel and Laurie. Bottom left, Raoul Van Damme admires Laurie's Kamasutra des grenouilles. Top right, Jean Secondi poses with a friend he found at the party. Top left, all jury members have lunch before the presentation (Sandrine Meylan, Laurent Coen) and online joined by Hannes van Wyk from South Africa.

It was also fabulous to meet Lauries family and friends who supported her throughout her academic journey.

The examination of a PhD is the end of a long journey and also a time to reflect on a set of great work accomplished by an individual working within a team. Laurie well deserves her new title, and we look forward to seeing what she will do with it.

Read the thesis:

Araspin, L. (2023) Thermal adaptation in an invasive frog (Xenopus laevis): impact of temperature on locomotion and physiology. PhD thesis. MNHN and Stellenbosch University