Which type of alcohol is the best?

We use alcohol for all sorts of things in biological sciences, but alcohol isn't always what it seems, and there are some important dos and don'ts. I got the idea and some of the facts for this blog post from posting by Cristy Gelling in 2012 that’s been sitting on my computer for 6 years. I’ve passed it on many times, but realised that I should do a blog post on it, because it’s useful information like this that you’re supposed to have on the lab blog!

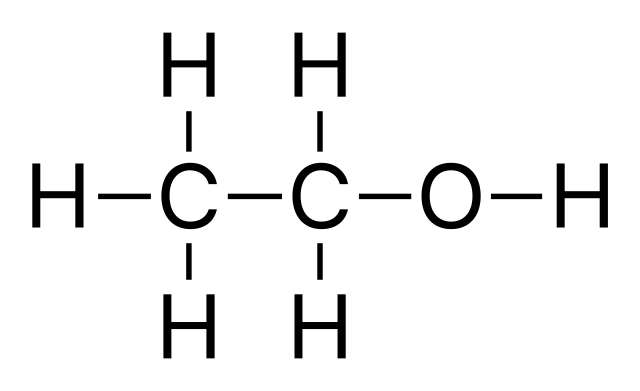

This is the chemical make-up of ethanol. I hope that it’s familiar to all of you as the two carbon molecules have their free spaces taken up with hydrogen, except one that has the -OH ending making it an alcohol. This is ethanol C2H5OH, because there are two carbons. One carbon would be methanol CH3OH, and more on that later.

Ethanol is familiar to most of us because it’s the same intoxicant that most of us use on ourselves when we’re trying to loosen up socially. It turns out that this really is a very poor choice of social intoxicant, because it is highly addictive and causes all sorts of diseases and problems, including the same social situations that we were hoping it’d make better. If you don’t do alcohol, then good for you, but if you do please make sure that you are very careful in how you poison yourself with this toxin as it’s really very dangerous. And it’s really important to say that you must never use lab ethanol to dose yourself (or anyone else). The reason is that lab ethanol is often close to being pure, and at those levels can do real harm. Moreover, lots of alcohol that’s kept in the lab isn’t ethanol, so you can do a lot of damage even when you were thinking…

Why do we use ethanol so much?

We use ethanol for pickling specimens (preserving bodies after formalin fixing), and for keeping tissue samples so that we can extract whole DNA later for molecular studies. The reason why it’s really useful is that it gets rid of water – dries the sample out. Water is really bad news for DNA, and other tissues. You should remember that water is a polarised molecule (one side is negative and the other positive). This means that it is very destructive and once an animal (or a piece of an animal) is dead, the water in the tissue will start destroying all of the molecules inside that we’re interested in. Very soon the rot will set in.

Ethanol grades:

95.6% ethanol

If your ethanol is locally distilled, then this is what you actually have. You aren’t going to have 100% ethanol through distillation because at this point the distilled ethanol has reached its vapour point (azeotrope) such that the vapour state has the same ethanol:water ratio as the liquid state.

A lot of people use ethanol for cleaning. This is because it’s a really good solvent – better than water at some things, and water is an awesome solvent. Oddly, I often see people cleaning benches with ethanol. This is really just moving the contaminants around on your bench, and not actually killing them. If that’s your objective then fine. Otherwise, use 10% bleach.

Absolute ethanol (99-100%)

This is expensive stuff, because as you’ve read above, it’s not as easy as distillation to get it. To get rid of that last 4.4% of water, the chemists use additives (such as benzene) to purify it by disrupting the azeotrope. You really only need absolute ethanol if you are doing something that has sensitivity to water (i.e. there must be no water), that calls for Analytical Reagent Grade (ANALR). Otherwise, use 95% which is all you’ll need for most of your lab work.

Remember that absolute ethanol is super hygroscopic (attracts water), so if you leave the lid off, you’ll won’t have absolute ethanol for long. For most of our work, best leave it on the shelf.

Preserving alcohol for specimens (70%)

Because water is naturally present in animal tissues, completely drying the specimen out in 95% ethanol will cause shrinkage and the tissues become brittle. Thus we use 70% alcohol when preserving specimens for long periods. Remember, that the preservation is about carefully managing the water content of the specimen. If you place a large fresh toad in 70% alcohol, the alcohol will become diluted by the water in the toad. The volume that you put the specimen in is critical. A large specimen in a small jar is mostly water before you’ve added any alcohol.

The best way to think about a specimen is a balloon full of water (most animals are 98% water). You need a large enough volume of water so that the volume of the balloon doesn’t change the concentration of the alcohol in the jar. Well, of course it will do exactly this unless you have a massive jar! Therefore, after a few days of the first soak, the alcohol must be changed. Otherwise, your specimen will rot. Well curated museum specimens will have their alcohol changed a few times in the first year, and then topped up on a regular basis.

Not everyone wants their specimens in 70% alcohol. This is because different taxa do best in different alcohol pickling states. If in doubt ask. For most amphibians, we want the final concentration to be 70% (but note that this isn’t what it’ll be when you first put the specimen and alcohol together).

How do you make 70% ethanol?

Just add 30% volume of distilled water to 70% volume of 95% ethanol. I know that it’s not exact, but this will be fine (for the dilution issue stated above). Never use absolute ethanol, because it’s super expensive. And it’s super expensive because someone has spent lots of time and effort removing all of the water. So you’d be a real imbecile to tip water into it.

Also remember that over time, 70% ethanol loses the alcohol (through evaporation) but keeps the water. So that really old bottle of 70% that’s been sitting on the shelf for years probably isn’t any more. If in doubt, make up some more.

What about denatured alcohol – methylated spirit – rubbing alcohol?

If you are out in the field and you need alcohol for work, the only thing that you are likely to be offered is denatured alcohol. This is because shops often aren’t allowed to sell 95% alcohol because folk are likely to do stupid things with it, as I’ve already warned you about above. If you want to know more about what’s inside, you can read it on Wikipedia. But is it useful to us?

For preserving bodies, denatured alcohol does a pretty good job. But make sure that you let the museum curator know that that’s what you’ve used as they’ll want to thoroughly rid the specimen of the denatured alcohol before putting it in their ethanol collection. However, some collections use denatured alcohol for all of their specimens. Thus, if you’re borrowing specimens to work on, it’s important to find out what the museum uses in order for you not to make a mistake when you top up the jar. If in doubt, do not use denatured alcohol.

Denatured alcohol is bad news for DNA, as the additives can interfere with the extraction and other applications (e.g. fluorescent labels used in microsats). You will find that some people do use it without problem. It maybe that it’s fine for your purpose, but if you have no idea don’t risk it. Use 95%.

Methanol

It’s not likely that you’ll need to use methanol. Methanol is a poison, so if you have to use it, treat it as such. It’s what people produce when distillation is incomplete, and has caused large numbers of people to go blind (extreme), or get really bad headaches (common). Methanol is often used in the denaturing process.