What’s the big idea?

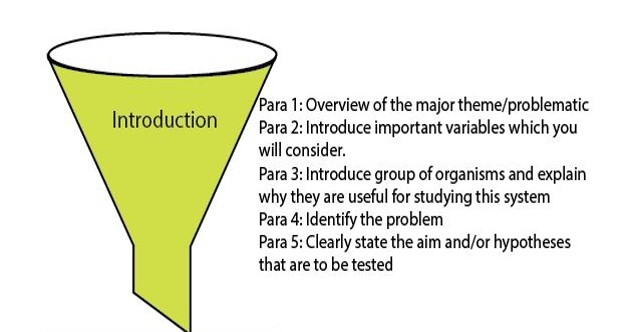

In previous blog posts (see here), I’ve talked about the importance of having a hypothesis, and building that hypothesis in a logical framework within the introduction (see here). The introduction serves to inform the reader about why this particular hypothesis was chosen, introducing both the response and determinate variables, as well as the presumed mechanism by which the hypothesis can be falsified (or upheld).

In this post, I take the lead from my recent talk for the Herpetological Association of Africa (see blog post here), in which I talked about the need for herpetologists to respond to bigger theories in biological sciences.

This message was the result of work done in the MeaseyLab (but not yet completed!) on invasion hypotheses, where we (Nitya, James, Sarah, Natasha and I) checked 850+ papers on alien herps to see which of 33 common invasion hypotheses they had tested. The answer was disappointing, with <1% having used an invasion hypothesis.

In my talk, I suggested that this might not be true only of papers on herpetological invasions, but also of herpetology in general (although I concede that some areas, such as herp physiology are actually quite good). Further, I contend that using these wider hypotheses or theories would actually be good for the authors concerned, as it would likely garner them a wider audience. Moreover, a greater number of biologists might come to realise how valuable reptiles and amphibians are as models in biology.

So where would we find all of these big ideas?

There are quite a few papers that synthesise hypotheses in various areas of biology. Here I provide two, but I will endeavour to add more as I come across them… so watch this space (although not too keenly).

The first is by Mark Velland on theories in community ecology

The next is by Jane Catford on hypotheses in invasion biology, but I encourage you to look for more up to date versions (the newest is by Enders et al 2018, but this’ll change in time).

Each of these papers will give you a list of big ideas, together with the citations for seminal papers that have built them. You will note that many of these theories are very old with many dating back to Darwin.

Of course, there are many ways to approach and test these theories, but if you don’t know about them, then your work may actually make a considerable contribution to upholding or refuting them, but go totally unrecognised. When the significance of your work isn’t realised, it’s unlikely that it’ll be widely read and used.

Let’s face it, if all the effort of the work that we put into papers is just going to get buried, then is it really worth it? The work that we do is also really expensive, so making it as relevant as we can to a wide an audience possible is something that we should be concerned about.

So, I encourage you to stand on the shoulders of giants by using big ideas in your introduction. Make sure that the data that you collect can actually be used to respond to some of these big ideas. Then make sure that you cite them, giving them the importance that they deserve (yes, even as key words) so that others can find your work, and you might even find that one day, your work has shoulders that are broad enough for others to stand on!

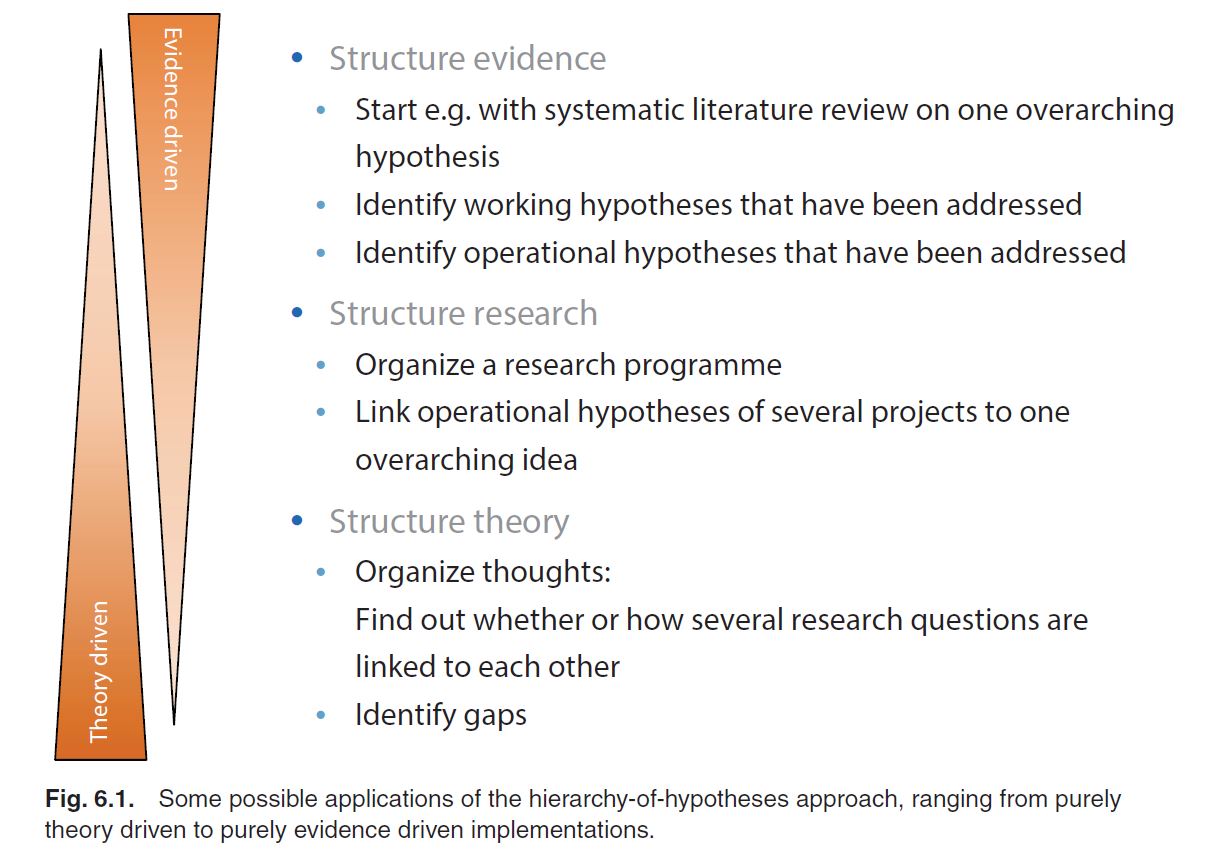

A useful structure for thinking about how hypotheses are structured was presented by Heger & Jeschke (2018) in what they termed the 'Hierarchy of Hypotheses'.

The take home message:

1. As herpetologists we are not engaging with theories from ‘the literature’

2. Herps are great models [even snakes]

3.We have a lot to donate to many areas of biology, but we need to engage

Reading the literature can really expand your mind and horizons. When undertaking a literature review [or when reviewing a paper], take the time to think about not only what has been tested, but what could have been.

Further Reading

Catford, J.A., Jansson, R. and Nilsson, C., 2009. Reducing redundancy in invasion ecology by integrating hypotheses into a single theoretical framework. Diversity and Distributions, 15(1), 22-40.

Enders, M., Hütt, M.T. and Jeschke, J.M., 2018. Drawing a map of invasion biology based on a network of hypotheses. Ecosphere, 9(3), p.e02146.

Vellend, M., 2010. Conceptual synthesis in community ecology. The Quarterly review of biology, 85(2), 183-206.

Heger, T. and Jeschke, J.M., 2018. The Hierarchy-of-hypotheses Approach Updated – a Toolbox for Structuring and Analysing Theory, Research and Evidence. In Invasion Biology: Hypotheses and Evidence. J. Jeschke and T. Heger eds. CABI. pp 38-45.