Talking to science denialists & the post-truth clan

I think we’ve all been in the situation where you are stuck in a room at some social event where you have to be on best-behaviour. But the person that most wants to talk to you is someone who just wants to tell you that everything you do is wrong and meaningless, and actually they hold the truth. They then proceed to tell you about some YouTube video that they’ve seen that convinced them that xxx (insert as applicable with moon landings, round earth, global warming, UFOs, all science or - especially these days - vaccines) are all bogus and/or are part of some conspiracy theory. You may get the feeling that the reason they’ve picked on you is that they know you are a scientist, and they basically want to sparr because they are sure that they can beat you. If you haven’t been in this position yet, it’ll happen to you someday soon, and in my experience is coming round more and more frequently.

Of course, the reason why this person thinks that they can beat you, is that they are planning to use the techniques that they’ve now trained themselves for using their ‘research’: i.e. watching whatever YouTube suggests now that its algorithm knows they are interested in this kind of thing. Their tactic will be to rattle off any number of tropes that if you have any inkling of an argument about why any one can be shown to be incorrect - they are ready to rattle off another. One of the major problems is that if you have an audience, especially an audience that is already sympathetic towards the denier, then your attempts to rebuff this person might actually backfire and reinforce the trope in them.

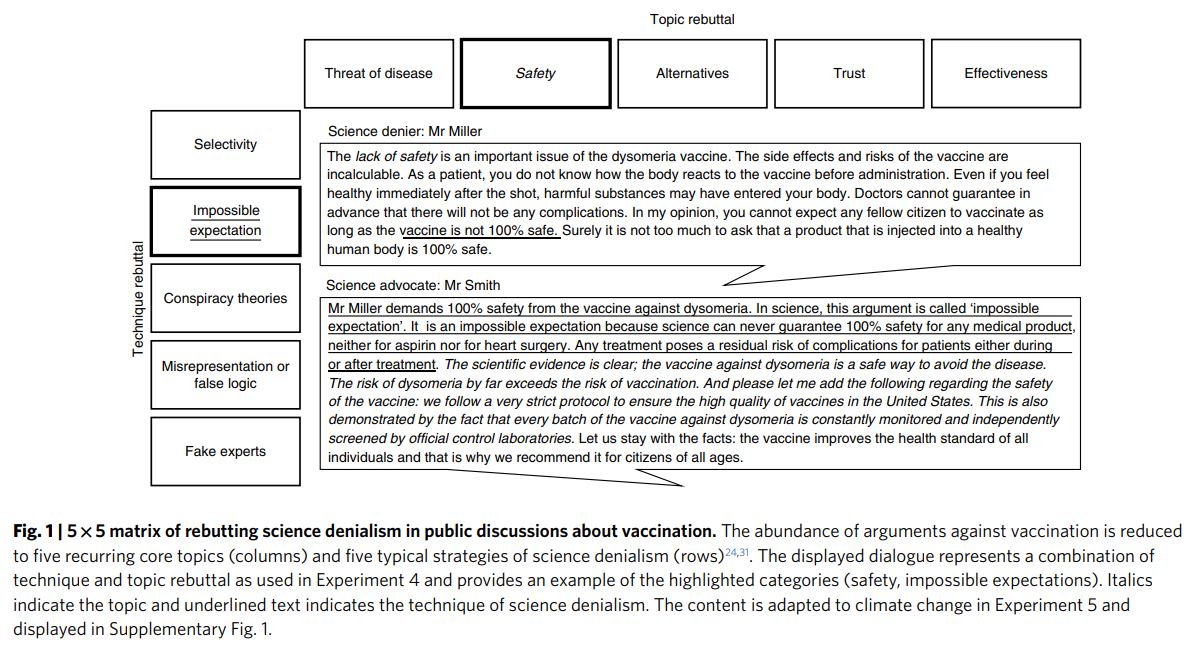

This blog article is based on the ideas that Philipp Schmid and Cornelia Betsch put forward in their 2019 paper (get ithere). They concentrate on the types of message content that are safe to pursue as a science advocate when in public discussion with a denier. Note that they do not cover two other important points: characteristics of the sender (you) and receiver (them). You should probably not expect the receiver of your argument to publicly change their minds, or admit they are wrong. What you can hope to do is to bolster the audience’s belief in science as a way of pursuing truth.

Topic rebuttal

Topic rebuttal is to have a set of facts on a subject to hand that refute or respond to the claims of the denier. This is tough for a lot of us, as we are often not conducting research in the particular area of interest of the science denier. Yet, many of us are aware of some basics that can at least slow down some of the more outrageous claims. In order to use topic rebuttal on your denier, you should be well prepared on the topic of the debate. But the way deniers take on scientists is by constantly switching to new topics until they find one that you aren’t aware of how to rebut. This might make it look to an audience as if they know more than you do. Once they find the topic that you can’t rebut - what then?

The other string to their bow is for every topic that you can rebut, just to claim that this is your opinion - making it look to the audience like that topic was an even draw - while they move onto the next topic. By pitching your response as equal to their claim, they can keep slipping through the topics until you get stuck, and then they will end up scoring one more than you. Or this is how it will seem to the audience.

This is when you can turn to technique rebuttal.

Technique rebuttal

Technique rebuttal will stand you in much better stead with an audience, because it will allow you to explain why the argument of the denier is wrong - not simply that they are wrong. Doing this, the audience will learn more about the nature of science, the need for evidence and that each topic is not an even score, but that you are the one who is scoring. Moreover, when the denier reaches a topic that you are not familiar with, you can explain that you don’t know the facts, but still go on to challenge the technique of their basis.

What we can be sure of is that your science denier will not be challenging you on the basis of a scientific study. This means that their argument needs another technique from which they can make their argument. Let’s look at each of these techniques in turn, and discuss how to spot and rebut them:

Selectivity

Observational selection, or cherry picking studies, has come up a lot during the pandemic as the media (and science deniers) have turned their attention to articles being posted on preprint servers. These are studies that have not even met the silver standard of peer review (see why I call Peer Review a silver standard and not a gold standardhere), and yet are touted by deniers as good evidence when ten other studies that do not show any effect are simply explained away as bad studies (also conspiracy theory - see below).

There are any number of reasons why we might expect good science to come up with a spurious results (i.e. Type I or Type II error, seehere). You can explain how science counters this with a consensus of studies. Importantly, is the concession that scientists will change their minds on topics if they find that their findings, or the consensus of findings of others, shows them to be wrong.

Impossible Expectation

Any argument that has an expectation that is unrealistic. As scientists we know that absolutisms are not real. Whenever someone tells you that something is 100% safe or 100% effective, they are (1) wrong and (2) their logic is questionable because there are no such extremes in safety or effectiveness. For example, vaccines are neither 100% effective, indeed many vaccines have quite low efficaciousness. Nor are vaccines 100% safe, there are usually a small proportion of people who will have adverse reactions. What is important though is exactly how small that group of people is. For vaccines in public circulation, adverse reactions are likely to be less than 1 in 10 000 or less than 1 in 100 000. This will be similar for other common medications (like the contraceptive pill that turns out to have quite a high level of adverse reactions that many people are prepared to accept). This is one of the easiest arguments to spot among denialists, and you can explain to most audiences in simple terms what an unrealistic or impossible expectation is.

Conspiracy Theories

Spotting a conspiracy theory is quite easy. When deniers claim that there are scientists who are being paid to publish their findings, and that the overwhelming majority of scientists are simply being paid off (typically by big pharma, governments, tech industry, etc.) - then you know that they are resorting to a conspiracy theory. Sadly, there are conspiracies out there. They are regularly perpetrated by big pharma, oil and tobacco companies - and these commercial interests are prepared to pay tame scientists to publish, often in inhouse journals. Governments too are known to ensure that their scientists publish studies that reinforce their views.

Hence, once you’ve spotted a conspiracy theory, you need to be careful how you respond. But you can go back to scientific consensus and work on how widespread results are unlikely to be the result of a conspiracy, and that these are more likely to be akin to cherry observational selection (see above).

Misrepresentation / False Logic

Denialists often fall into traps around faulty logic. You can find a list of thesehere. The most common errors are that one statement does not logically follow from the first.

Another common mistake is that ‘something happened after, so it was caused by’ argument. This is a surprisingly common explanation, but fails to take an objective look at total evidence. This is especially common in people’s personal insight. For example, they took a vaccine, and then got sick. Therefore, the vaccine made them sick. Of course, there are lots of levels of this debate, including that there is a small chance that they really did have a reaction to the vaccine, but this doesn’t make the vaccine unsafe, because it is expected and experienced by a great many people.

Deniers will often eschew statistics, as being a way that lies are told. Again, there is some small amount of truth here, but large effects cannot be explained by faulty statistics, and once again the scientific consensus here is a valid response.

Fake Experts

The last technique that deniers often use are fake experts. Fake experts are real - and by this I mean that there really are people who are employed by universities that pedal bullshit (seehere for how to spot a bullshiter). When I worked as a post-doc for University of the Western Cape back in the late 1990s, there was a Professor employed in their Department of Zoology who had a career giving talks on alternative medicine. His experiments would never get published, because he failed to conduct controls or had very few replicates. But this did not stop him peddling his untruths around the planet. He would be invited to give talks to more people in more places than any scientist I’ve ever known. There is another retired Senior Lecturer from Stellenbosch University that sells fake kits to repel invasive polyphagous shot hole boring beetles. No doubt he has made a packet from claiming to be from the university.

An argument built on a fake expert is rather like a naive version of observational selectionism (see above). They are relatively easy to spot, and then simply invite a discussion with the fake expert. Ask about specific studies that the fake expert has conducted, their results and where they are published. Expect to hear more connections to observational selection and conspiracy theories.

How to know when what you smell is bullshit

Carl Sagan wrote a great list that he called his ‘baloney detection kit’ (and I have renamed above). This is well worth reading because it is something that you can help teach a public audience into how not to get duped by a science denier again.

Do take a look at the paper by Schmid & Betsch (2019) and read about experiments that they conducted on technique rebuttal and how effective the approach is with science denialism.

Schmid, P. and C. Betsch (2019) Effective Strategies for Rebutting Science Denialism in Public Discussions.Nature Human Behaviour3: 931–39.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0632-4.