All toads are equal, but some are more equal than others

When conducting an eradication campaign, it seems obvious that you should go out and collect all the individuals you can find. But could collecting some individuals be more important than others? This question is especially important when it comes to animals with complex life-cycles where the larvae and adults inhabit different parts of the ecosystem. We asked this question of the Guttural toad eradication in Cape Town, and received some surprising answers.

Guttural toads lay large numbers of eggs, and their tadpoles inhabit garden ponds in the low-density, high-income suburb of Constantia. Meanwhile, the adults cruise around the gardens looking for insects and snails to snack on. For the people charged with their control, they can either spend their time cruising in the shrubberies looking for adult toads, or go to the ponds with nets and scoop up tadpoles and strings of eggs. Or of course, they could do both. But what is the best strategy?

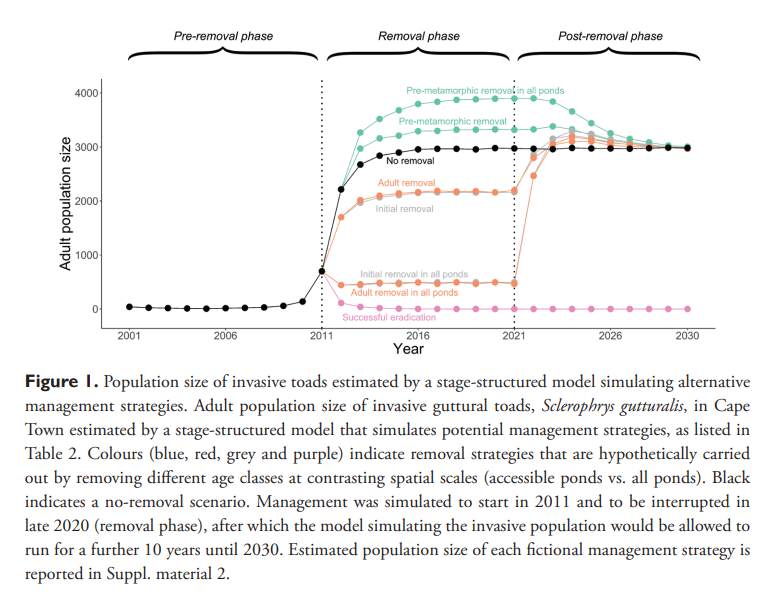

Giovanni Vimercati built a mathematical model of the Guttural toad population in Constantia to answer this problem (see also Vimercati et al. 2017a,b). Recently, Gio used this same model to answer the question of which life-history stage of these toads should be targeted by people trying to control the population. Because there is strong competition between tadpoles and metamorphs, Gio found that any attempts to remove these aquatic life-history stages resulted in an increased number of toads in the population. The counter-intuitive result is known as the ‘hydra effect’ - where cutting off some heads simply makes more grow. In the case of the Guttural toad, the removal of some of the aquatic stages increases the rate of survival and fitness of those that remain.

The model has the advantage that it can be run forwards to see what happens to the population given different control regimes. The mathematical model results told us that to maximise the impact of time spent controlling toads, concentrate on collecting adults. Adult removal has a far greater impact on the total population.

To read more:

Vimercati G, Davies SJ, Hui C, Measey J (2021) Cost-benefit evaluation of management strategies for an invasive amphibian with a stage-structured model. NeoBiota 70: 87–105.https://doi.org/10.3897/neobiota.70.72508

Other publications on this model are:

Vimercati, G., Davies, S.J., Hui, C. & Measey, J. (2017) Does restricted access limit management of invasive urban frogs? Biological Invasions19: 3659-3674.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-17-1599-6

Vimercati, G., Davies, S.J., Hui, C. & Measey, J. (2017) Integrating age structured and landscape resistance models to disentangle invasion dynamics of a pond-breeding anuran. Ecological Modelling 356: 104–116https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2017.03.017