Racism in Science: take away lessons from the E. O. Wilson debacle

Racism is still a persistent reality in 21st Century human societies. Those societies include scientific and academic institutions, even though we all would rather that those labels could never be associated with us or our approach to the world about us. Like other problems in academia (seeMeasey 2022for a miscellaneous group of issues from bullying to fraud), our best approach is to be aware of issues with racism and not to pretend that they don’t exist.

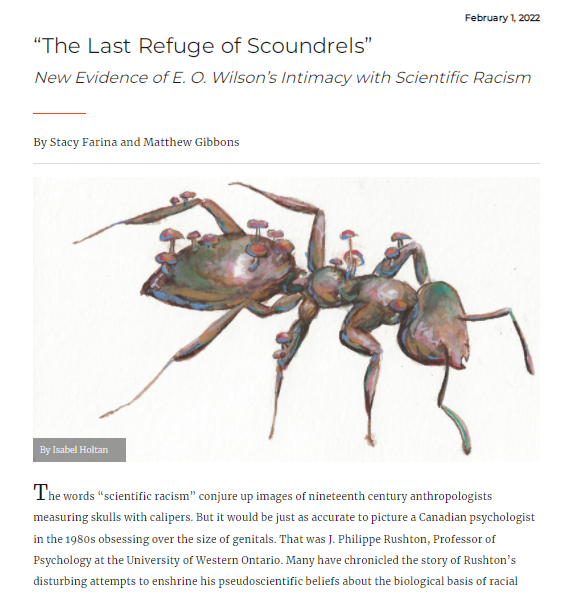

This blog post is written to highlight the lessons that we need to learn from the recent (and not so recent) revelations about the racist beliefs of E. O. Wilson. There is no doubt that E. O. Wilson was a great ecologist. His ideas and ecological insight will continue within the scientific literature many decades into the future. But following new revelations in an article by Farina and Gibbons (2022), we can no longer have any doubt that E. O. Wilson was also a racist, and actively used his influential position to promote his racist views albeit through third parties in order to avoid exposing himself.

The article by Farina & Gibbons (2022) is well worth reading, as they provide the evidence for E. O. Wilson’s views and also the way in which he corrupted the academic system, through publishing gatekeepers, to promote ‘scientific racism’ of those who espoused it, and defended them when they were threatened.

Take-away lessons

It is all too easy to admire scientists (and others in society) who lead their fields and achieve levels of greatness in their own lifetimes, and sometimes beyond. Today, that global admiration and recognition often results in those individuals reaching levels at which they are unassailable in their societies. Such was the case with E. O. Wilson. Following his death in December 2021, a critical article in New Scientist by Monica R. McLemore (2021) was lambasted by many scientists on social media for suggesting (again) that E. O. Wilson was a racist - a claim that they considered baseless. But this wasn’t the first time that E. O. Wilson had been called a racist, and it was something that he was acutely aware of and did his best to hide from colleagues and the public (Farina and Gibbons 2022). The importance of the article by Farina and Gibbons (2022) is that they demonstrate the evidence for E. O. Wilson’s activities, and his complicity with others who shared his beliefs.

This is not the only example where our current academic system has become corrupted by those who reach the highest ranks of their profession. Those individuals become so highly regarded by their colleagues and institutions that they are cocooned and protected against any accusations of wrong-doing. This is mostly as these positions come with such power and influence that they command an income to their institutions that cannot be threatened. Another prominent example is that of academic fraud (seeMeasey 2022for examples). Even when individuals are exposed by their colleagues and former students, their institutions continue to protect and defend them because they represent a source of income that is unparalleled by their less controversial and lower income colleagues. Indeed, for as long as we promote the winner-takes-it-all attitude to funding science, we can expect that there will be individuals that use and exploit the system for their own gains (seeHeard 2015for a nice perspective on this problem). Sadly, those who exploit the system to the highest level, will also be protected by their institutions.

In a nutshell, as scientists we are all human. There are those among us who will have bizarre and ugly beliefs, including racism. We cannot pretend that these prejudices will go away with an old generation, they will continue to morph and change as time goes by. What we can do is to remove the professional inequalities that currently exist in hiring and publishing science, and be aware that no matter how high our colleagues reach in greatness within their own fields, it does not mean that they cannot be wrong.

Further Reading

Fainra S. & Gibbons M. (2022) The Last Refuge of Scoundrels. Science for the People Magazine 25. https://magazine.scienceforthepeople.org/online/the-last-refuge-of-scoundrels/

Heard, S. (2015) Why grant funding should be spread thinly. Scientist Sees Squirrel Blog Post:https://scientistseessquirrel.wordpress.com/2015/05/12/why-grant-funding-should-be-spread-thinly/

McLemore, M.R. (2021) The Complicated Legacy of E. O. WilsonScientific American,https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-complicated-legacy-of-e-o-wilson/

Measey, J. (2022) How to publish in Biological Sciences: a guide for the uninitiated. CRC Press, Boca Raton. ISBN: 9781032116419http://www.howtopublishscience.org/