Academic capture

The 21st century has brought with it some new terms that have not been welcomed. One of these was ‘state capture’: when the government and its institutions’ policies and laws are significantly influenced by private individuals and their companies for profit. This became a hallmark of governments in Europe (Hungary, Bulgaria, western Balkans), several Latin American countries (Argentina, Bolivia, Columbia and Mexico) and South Africa. Some have also suggested that the USA under Donald Trump was undergoing ‘state capture’.

The lament of academics that publishers are profiteering from their labours through charging ever increasing sums to access their work are familiar to most of us. We are caught in a system whereby our employers judge us by the prestige of what we output, and typically these outputs are publications published by the same profiteering publishing companies. Choosing to opt out would result in academic suicide for any Early Career Researcher who cannot show that they are capable of publishing in upper quartile journals. Similarly, publishing in the highest ranked journals can facilitate and define a career - so much so that some academics are prepared tocommit fraudin order to publish there. Moreover, pushing for increasingly high metrics perpetuates dynasties ofbad sciencethat jeopardise the centralscientific tenets of rigour, reproducibility, and transparency.

Björn Brembs and colleagues have just revealed a much darker side to this story in apreprint on Zenodo. In it, they describe what we could describe as the incipient capture of all academia by the same four publishing giants that are dominating the publishing conundrum described above. In it, they describe the shift of profits by these companies from publishing towards data. We know that Elsevier owns Scopus and so are able to drive the listing of all of their own journals therein, and ensure that they attain maximum benefit from inflation of metrics. But did you know that the new academic database on the block, Dimensions, is owned by publishing supergroup SpringerNature?

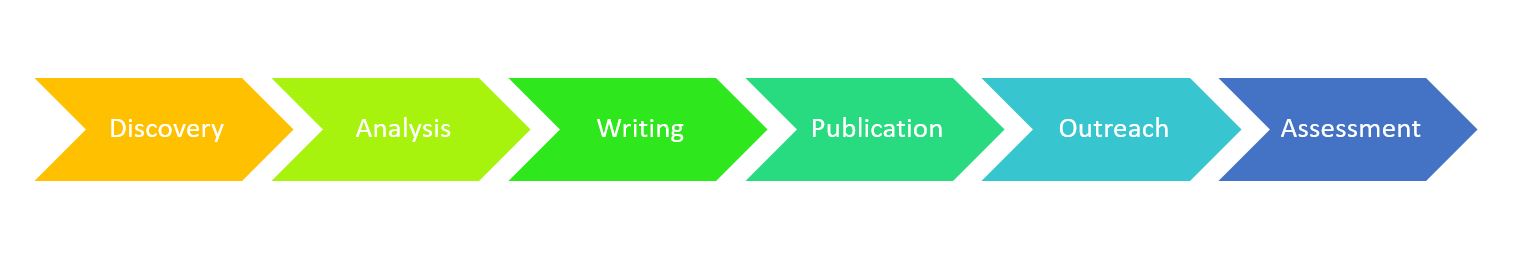

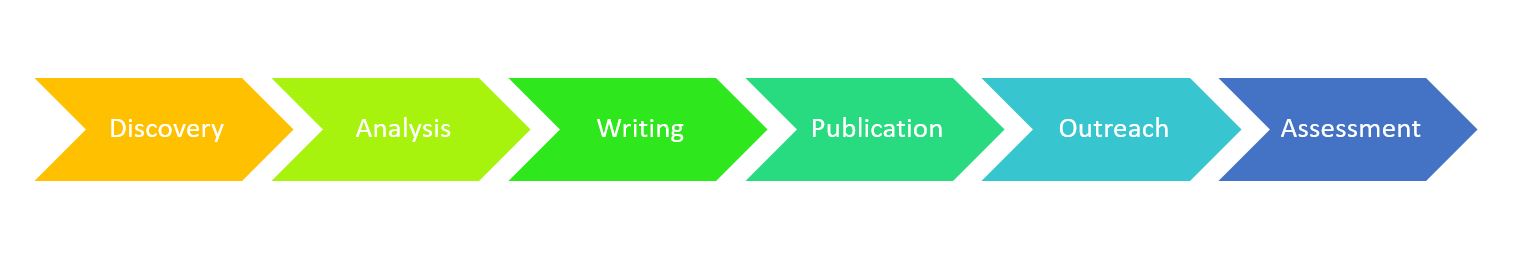

When an institution subscribes to one of these databases, they also subscribe to a whole set of access to metrics that inform them about their own academics, and any prospective academics that they may want to employ. Owning the company that makes the metrics, makes sure that the publisher gets a controlling stake in the future of publishing in that institution. But the most startling revelation by Brembs et al. is that discovery and publishing are just the two ends of what these four publishing houses are attempting to acquire: the complete academic workflow.

Figure 1. The academic workflow undergoing capture

In the central figure of their manuscript, Brembs et al. provide a breakdown of each of the companies acquired by Elsevier, SpringerNature (Holtzbrinck), Wiley-Atypon and Taylor & Francis. It might not surprise you to know that Elsevier and Holtzbrinck are far ahead of the others in terms of completing their work-flow capture. Holtzbrinck, for example, also own Digital Science, a new company that owns Dimensions, Elements and Altmetrics. This captures the discovery, outreach and assessment ends of the work-flow. They also own Overleaf (the writing component) and a raft of analytical tools. It goes without saying that they have all Springer, BMC and Nature journals in the publication sector.

And once they’ve captured the workflow?

We should be aware by now that companies that capture a lot of data are in a commanding position to find plenty of customers. Who do you think are the customers for all publicly funded science?

Imagine the worst implications of theCambridge Analytica data scandal, and then apply this to the entire academic workflow. Not a pretty picture for sure. But it’s one that should strike fear into the hearts of all academics. This is happening now, and you and your research is feeding it. These publishers don't even need to install spyware onto our computers as their tools do it all for them. Once collected, individual data on employees can be sold to employers, or third parties interested in our research topics. At least with Cambridge Analytica you had to be duped into giving over your data. Right now, we are giving our entire academic workflow into the hands of the same people that have prompted our greatest obstacles to free and open science.

For those of us who have lived through state capture, we felt powerless and could only watch as institutions were plundered. Right now, we are willing participants in the capture of our own academic freedom.

Academic capture: when the institutions’ policies are significantly influenced by publishing companies for their profit.

How can we prevent academic capture?

There is a growing community of academics that are pushing for Open Research, and in particularOpen Source Tools. Always use open source software, and avoid using any software offered for free by publishers (e.g. Mendeley, Overleaf, Peerwith, Authorea, etc.).

Where possible, we should be avoiding publishing work with the big four academic publishers, and when necessary ensuring that they do not hold any rights to our data or our work. Support smaller publishers where possible, and promote their use in your scholarly societies. If possible, advocate for diamond open access using platforms likeOverlay Journalswith any journals that you conduct work for. Discourage your library from subscribing to databases run by big publishers.

An economic solution, offered by Brembs et al., is to ensure that publishers can be replaced through competition. In this vision, currently adopted by funders such as the EU’s Horizon 2020, publishers win contracts to publish research and bid to win consecutive contracts with no right to being locked-in. Although it is possible that market forces may move profit from unreasonable numbers towards actual costs, it seems unlikely that our big academic publishing companies will ever release their grip on profits. Instead, we can expect them to fill in the missing gaps in our academic workflow, and increase the rate at which they capture our data.

Reference:

Björn Brembs, Philippe Huneman, Felix Schönbrodt, Gustav Nilsonne, Toma Susi, Renke Siems, Pandelis Perakakis, Varvara Trachana, Lai Ma, & Sara Rodriguez-Cuadrado. (2021). Replacing academic journals.https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5526635