Submitting a paper for review

In this week's lab meeting, we discussed the process of submitting a manuscript to a journal, and what happens once this is done. Here, I’ll briefly summarise some of the points that were made in the meeting:

- Targeting journals for submission: there are a lot of journals out there, and you need to make sure that you are submitting your paper to a journal in the right subject area. Your advisor should help with this, but if you are starting from scratch you can list journals in areas such as ecology or evolution using Web of Science or Scopus and rank them according to impact. This gives you a proxy list to discuss with your advisor and co-authors when preparing a manuscript for submission. Keep the agreed list, as if you are rejected from the first journal you’ll know where to go next.

-

- Take special note of journals that require fees (Article Processing Charges: APC), either for Open Access or as page charges (some US journals). See blog posts about Open Access and APCs here, here and here.

- The MeaseyLab policy is not to use research funds to pay for publishing, so you’ll need to make special provision for finding this money if you really want to submit to a journal that has an APC.

- Prepare your manuscript (ms) according to the journal guidelines: this may require a lot of work especially if the journal requires full formatting on first submission. Some journals require additional items such as graphical abstracts, so make sure that you know what is needed.

-

- Very important to note are any word limits (including for the abstract), and potential caps on number of citations.

- After approval from your supervisor, circulate this final version among your co-authors. This is a good time to gather the needed meta-data for submission.

- You’ll (usually) need a letter to the editor, key-words, recommended (or opposed) reviewers, and addresses (with ORCID) for all authors. These should all meet the approval of your co-authors.

- Uploading your ms to the editorial management software requires time and preparation. Give yourself a good couple of hours for this process, as it can be frustrating.

- Once submitted to the system, your manuscript is usually checked before being passed to the editor. You may get it sent back if the meta-data is wrong.

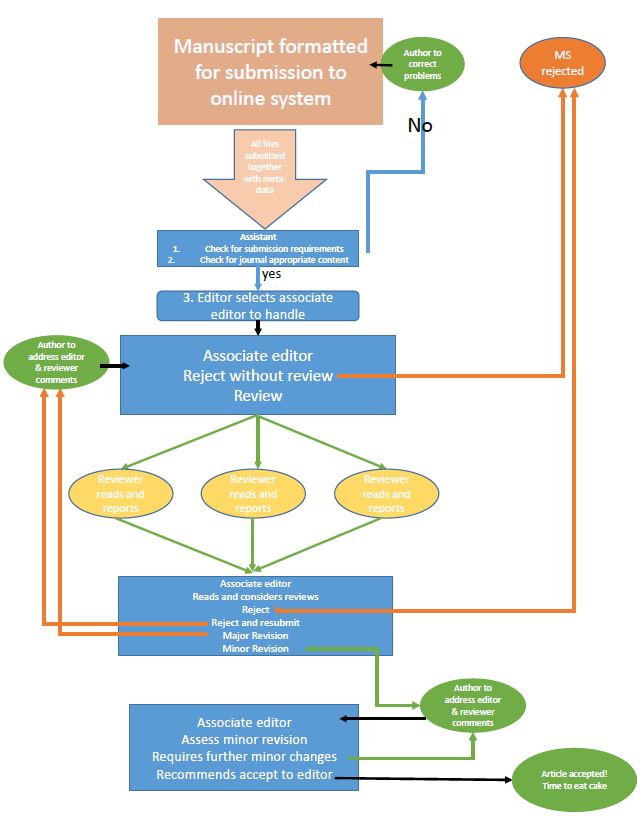

- Inside the management systems, there are various workflows, and here I’ll describe something typical, although others do exist. Once the editor (often Editor in Chief) has your ms, they will decide which associate editor (AE) will handle it.

-

- The AE should read the ms and may reject it if they feel that it won’t make it through review. An AE rejection isn’t great as they don’t always have the best experience in knowing what will and what won’t make it through. The editor usually has more experience. Hopefully, this won’t have taken long (1-2 weeks) and so won’t be very painful. This rejection may be fair or unfair, but it’s hard luck and there’s nothing much you can do except return to step 2 (above).

- Normally, your ms will be sent out to review and you can expect to wait 4-6 weeks (good), but sometimes up to 3 months, for a decision. If it’s away for over 3 months, you should definitely make a query on the editorial management system.

- Once back from review, you’ll get an email from the editorial management system with the decision.

-

- If it’s rejected, take the comments of the reviewers on board. Think about it for a couple of days, and then set about revising the manuscript. However unfair you think the reviewers have been, there should be some important messages for you to consider carefully and discuss among the co-authors before going back to step 2.

- Reject and resubmit: This is a category that means you need major revision, but the journal doesn’t want the time that it takes to do this on their stats. In many journals, this result has replaced ‘major revision’. Back to step 3 with a track changes manuscript and response letter to reviewer comments.

- Major revision: essentially the same as 6b. Both 6b and 6c result in your ms being reviewed again. You’ll need to carefully prepare both the ms and the response to reviewers as the reviewers will see both. Back to step 3 with a response letter.

- Minor revision: is unusual at this stage, but your ms should now only be assessed by the AE, so you should address your responses to them.

- If you are resubmitting, aim to prioritise this to get it done in 2 to 3 weeks if possible.

-

- The reason is that the same reviewers are likely to be willing to look at your ms again within a month, and will remember all the points that they made. Similarly, the AE will remember all of the issues that they had. It’s hard to stress how valuable this is, as keeping it all fresh will result in a swift response.

- If you don’t or can’t manage to get your responses back quickly, you might expect a rocky ride through the review process when you go back for the second round. The reviewers you had before might not be available, but the AE will be obliged to have at least 2 reviews again. This means that you may get new reviews. New reviewers are likely to throw up new issues, and could result in your ms getting rejected at this stage, or that you’ll have another major review decision, sending you back to step 3 with a track changes manuscript and response letter to reviewer comments. This drags the whole process on for much longer and reviewers and AEs are likely to look less favourably at your ms.

- A better result is when there are only minor revisions. In this case the ms is simply bouncing between you and the AE and even if this happens more than once, it’s fine as long as you can keep the response time reasonable (within a couple of weeks).

- Hopefully by now your ms has been accepted, and you are entering the last stages of the process. Your accepted ms should be sent to the publishers for typesetting, and you can get the proofs back very quickly (for some publishers). Most demand that the proofs are returned very quickly (often within 48 hours), and you should try to prioritise this if you can. If you can, please also send it to the co-authors. The more eyes the better at this stage for spotting errors. Don’t expect to be able to change a lot in the proof process, it’s really just for catching errors. Carefully check all figures, tables and legends. It’s not unknown that typesetters cause problems when they make proofs (tables can be disasters).

-

- Check the acknowledgements again and make sure that your funders are included. You should always acknowledge:DSI-NRF Centre of Excellence for Invasion Biologyfor their support. I also suggest adding in the reviewers (even if anonymous) for their help in improving the ms.

- If you (or a co-author) spot a fundamental error with your data or analyses at this point (or any of the other steps above), you should discuss it with all co-authors and decide what to do. It’s better to withdraw the ms than to have to retract it later.

The peer review process is not ideal, but it is worth remembering that it’s there to help improve your manuscript. Different reviewers have different styles of review, and these tend to be culturally distinct around the planet. You should be aware that apparently ‘rude’ comments by reviewers might simply be attempts at humour. Try not to be disheartened by anything that you read in a reviewer’s comments. You never know the conditions that they were in when they read your manuscript, or what their day was like. This is also a point to consider when writing a review for a paper, but let’s tackle that in another blog post.