Making a presentation from your research proposal

In theory, it couldn’t be easier to take your written research proposal and turn it into a presentation. Many people find presenting ideas easier than writing about them as writing is inherently difficult. On the other hand, standing up in front of a room of strangers, or worse those you know, is also a bewildering task. Essentially, you have a story to tell, but does not mean you are story telling. It means that your presentation will require you to talk continuously for your alloted period of time, and that the sentences must follow on from each other in a logical narative; i.e. a story.

So where do you start?

Here are some simple rules to help guide you to build your presentation:

- One slide per minute: However many minutes you have to present, that’s your total number of slides. Don’t be tempted to slip in more.

- Keep the format clear: There are lots of templates available to use, but you’d do best to keep your presentation very clean and simple.

- Be careful with animations: You can build your slide with animations (by adding images, words or graphics). But do not flash, bounce, rotate or roll. No animated little clipart characters. No goofy cartoons – they’ll be too small for the audience to read. No sounds (unless you are talking about sounds). Your audience has seen it all before, and that’s not what they’ve come for. They have come to hear about your research proposal.

- Don’t be a comedian: Everyone appreciates that occasional light-hearted comment, but it is not stand-up. If you feel that you must make a joke, make only one and be ready to push on when no-one reacts. Sarcasm simply won’t be understood by the majority of your audience, so don’t bother: unless you’re a witless Brit who can’t string three or more sentences together without.

Keep to your written proposal formula

- You need a title slide (with your name, that of your advisor & institution)

- Several slides of introduction

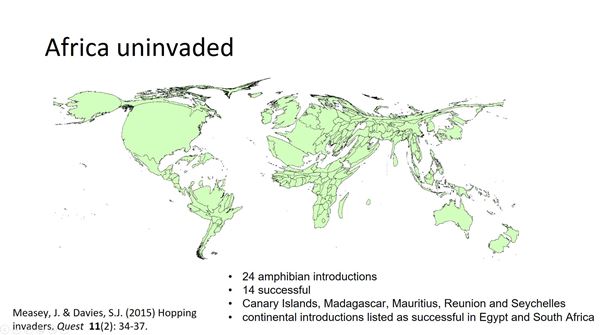

- that put your study into the big picture

- explain variables in the context of existing literature

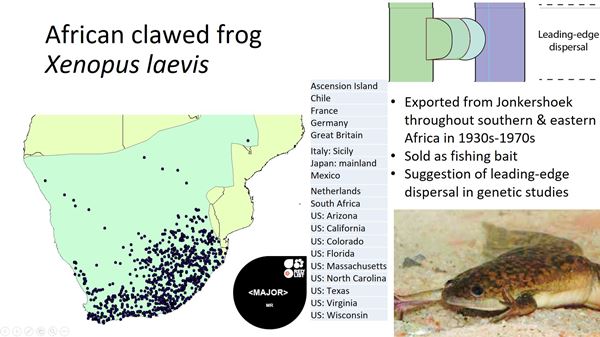

- explain the relevance of your study organisms

- give the context of your own study

- Your aims & hypotheses

- Methods & Materials

- Images of apparatus or diagrams of how apparatus are supposed to work. If you can’t find anything, draw it simply yourself.

- Your methods can be abbreviated. For example, you can tell the audience that you will measure your organism, but you don’t need to provide a slide of the callipers or balance (unless these are the major measurements you need).

- Analyses are important. Make sure that you understand how they work, otherwise you won’t be able to present them to others. Importantly, explain where each of the variables that you introduced, and explained how to measure, fit into the analyses. There shouldn’t be anything new or unexpected that pops up here.

- Expected results

- I like to see what the results might look like, even if you have to draw graphs with your own lines on it. Use arrows to show predictions under different assumptions.

- Budget

- Timeline

Slide layout

- Your aim is to have your audience listen to you, and only look at the slides when you indicate their relevance.

- You’d be better off having a presentation without words, then your audience will listen instead of trying to read. As long as they are reading, they aren't listening. Really try to limit the words you have on any single slide (<30). Don’t have full sentences, but write just enough to remind you of what to say and so that your audience can follow when you are moving from point to point.

- Use bullet pointed lists if you have several points to make (Font 28 pt)

- If you only have words on a slide, then add a picture that will help illustrate your point. This is especially useful to illustrate your organism. At the same time, don’t have anything on a slide that has no meaning or relevance. Make sure that any illustration is large enough for your audience to see and understand what it is that you are trying to show.

- Everything on your slide must be mentioned in your presentation, so remove anything that becomes irrelevant to your story when you practice.

- Tables: you are unlikely to have large complex tables in a presentation, but presenting raw data or small words in a table is a way to lose your audience. Make your point in another way.

- Use citations (these can go in smaller font 20 pt). I like to cut out the title & authors of the paper from the pdf and show it on the slide.

- If you can, have some banner that states where you are in your presentation (e.g. Methods, or 5 of 13). It helps members of the audience who might have been daydreaming.

Practice, practice, practice

- It can’t be said enough that you must practice your presentation. Do it in front of a mirror in your bathroom. In front of your friends. It's the best way of making sure you'll do a good job.

- If you can't remember what you need to say, write flash cards with prompts. Include the text on your slide and expand. When you learn what’s on the cards, relate it to what’s on the slide so that you can look at the slides and get enough hints on what to say. Don’t bring flashcards with you to your talk. Instead be confident enough that you know them front to back and back to front.

- Practice with a pointer and slide advancer (or whatever you will use in the presentation). You should be pointing out to your audience what you have on your slides; use the pointer to do this.

- Avoid taking anything with you that you might fiddle with.

Maybe I've got it all wrong?

There are some things that I still need to learn about presentations. Have a look at the following video and see what you think. There are some really good points made here, and I think I should update my example slides to reflect these ideas. I especially like the use of contrast to focus attention.