How to write a hypothesis

This is a sticking point for many students. We are used to using and writing questions and statements in day to day communications, as well as reading popular media. But hypotheses (the plural of hypothesis) only rarely float across our desks. So how do we write one, and how do we know if our hypothesis is good?

Although I’m going to write about what I think, there is already some good information out there on the web, and it’s worth looking at this too: (e.g. Wikihow, Wikipedia, etc.). There’s also some dodgy stuff, so read critically.

What is a hypothesis?

A hypothesis is a statement of your research intent. It tells the reader (because just like all of your other written work, it has an audience who reads it), what you planned to do in your research. But there’s a little more to it than this. The hypothesis becomes a part of the scientific method if it is testable, and informed from previous published work on the subject.

Yes, your hypothesis must be informed by the literature, which is why you spent so much time and effort crafting your introduction to inform your reader of the same. This is also why your hypothesis usually comes at the end of your introduction, because you spend all of the introduction telling your reader about it (see blog entry here). There’s not much point in writing more after the hypothesis, because once your reader has read that, they are ready to learn about how you went about testing it (in the Materials & Methods). The other important point to make is that the literature should dictate how you write your hypothesis, and the variables that you include. If, for example, you know that temperature is the most important variable but all of the literature suggests that it is oxygen, you can’t ignore oxygen and you should also frame your hypothesis using this variable (you can have more than one hypothesis after all!). In this case, you will also need to provide a sufficient introduction to temperature as a variable to justify its inclusion in your hypothesis. Perversely, your aim is not to prove that your idea is right, but to show that the hypothesis is wrong.

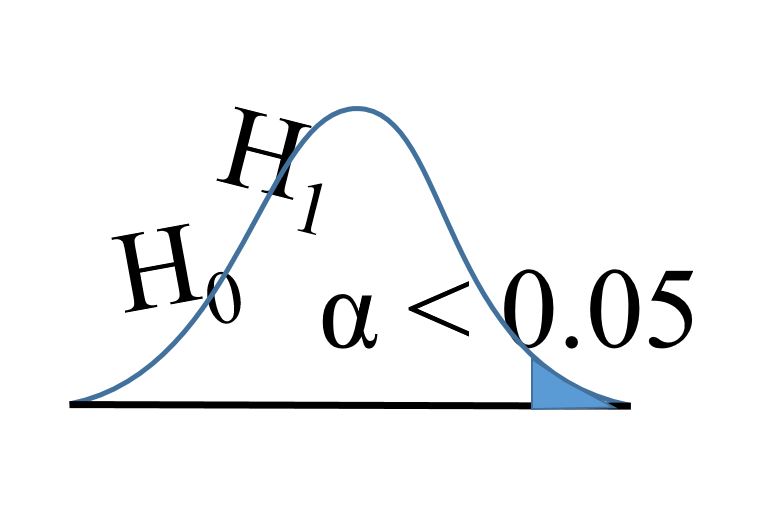

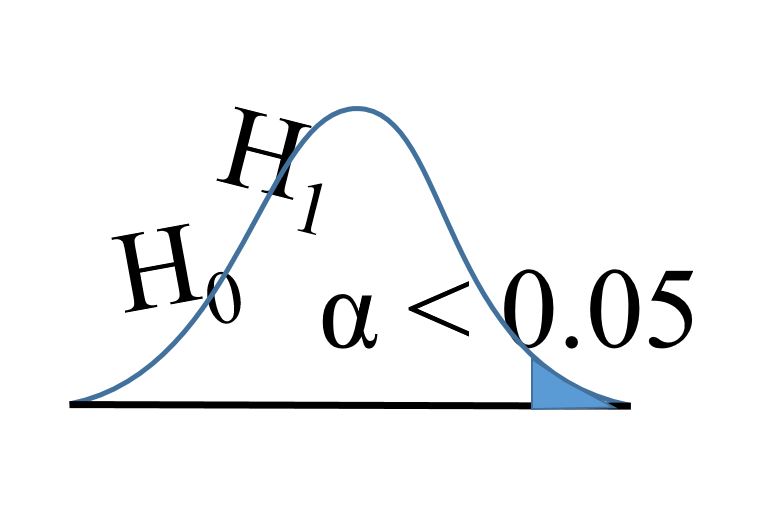

We usually try to write a hypothesis that is falsifiable: i.e. you can prove (usually using statistical tests) that it is not correct (or at least show that the likelihood that it is correct is very low). That’s why it is conventional to provide the ‘Null hypothesis’ that is the falsified version of the statement, suggesting that there is no relationship between the variables you have proposed to measure. The convention is to label this H0, while the ‘alternative hypothesis’ (the one that says your variables are related as you suggested) is written as H1. You can write you alternative hypothesis to show the directionality of your tested variables, or simply that there is a relationship.

Most importantly, your hypothesis must come first, before you do the experiment or study! Setting the hypothesis after the work is already done is fraudulent, and goes against the scientific method. Obviously, it isn’t fair to pose the hypothesis once you already know the answer. This is why there is so much emphasis put on formulating your hypothesis during your research proposal. Getting it right will determine what you do and how you test it. If you think of an extra hypothesis that would be really useful to test once you’ve already done your study, you can conduct a post hoc test, but this should have more stringent levels of statistical assessment.

Writing a hypothesis isn’t easy, but it is essential and once you’ve understood what to do, most of the rest of what you are writing for should make sense.

What a hypothesis isn’t

It is not a question and so should never have a question mark after it.

It isn’t really a simple prediction: if this then that. You will see many times on the internet that hypotheses are explained in this simple predictive framework. I say that it isn't 'really' a simple prediction because these are not good hypotheses. They lack the mechanistic and scholarly aspect of a good hypothesis, which is what we want to achieve.

A formulaic way to start writing your hypothesis: “If… then… because…”

Above, I emphasised that you must have introduced all the variables that you plan to use to test your hypothesis in your introduction. This usually comes in the second paragraph (see blog entry here), where you emphasise the utility of the dependent variable/s (what you are planning to measure) and your independent variable (what you will manipulate). Both of these variables should then feature in your hypothesis. Next, by paragraph four you will have identified the problem that you are interested in tackling. In addition, your introduction will provide all of the pertinent literature that has relevance to this hypothesis, giving the all important context.

A simple way to consider making your hypothesis is to adopt an “If… then… because…” construction where you add in your problem statement using your independent variable after ‘if’ and your prediction using your dependent variable after ‘then’, and finally the expected mechanism after ‘because’. Using our example above with the “If… then… because…” construction, we would say: “If environmental temperatures in which tadpoles develop are increased then tadpole development rate is faster because they follow the classic metabolism of ectotherms”. Both independent variable (temperature) and dependent variable (tadpole development rate) are present in this hypothesis, and the predicted relationship between them is clear. In addition, the causal mechanism is stated. You can watch a video about using the “If… then… because…” construction here, or read more here. I say that this is a formulaic way to start writing your hypothesis, because it usually ends up as an inelegant statement, which can be better refined for a reader. A citation for your stated mechanism might also help clarify exactly where the justification for this comes from.

A good hypothesis will often take an existing hypothesis further, to try to better refine the knowledge on a subject. Hence, it is perfectly acceptable to state that you are building on existing hypotheses (and giving the appropriate statement) when making your own.

How to evaluate your hypothesis

Once you’ve written your hypothesis, how do you decide whether or not it is good? To do this, you might think that you need plenty of experience (and yes, that does help). But really, you just need to look for the elements that are discussed above. So once you’ve written your hypothesis, try to objectively answer the questions below (for more see Bartos 1992 and here):

- Is there a clear prediction (if… then… statement)?

- Does the prediction use independent and dependent variables correctly?

- Is the mechanism supported by the literature?

- Is the hypothesis testable/falsifiable?

- Does the hypothesis use concise wording and precise terminology?

If your hypothesis meets all of the criteria above, then you’ve done a good job!