Why should an editor read your submission?

There is a worrying increase in poor editorial decision making, without any basis, because editors are not reading submissions.

When a manuscript is submitted to a journal, the submission goes to either the editor-in-chief or a handling editor based on the key words or journal section implied during submission. In some journals (like PeerJ) the submissions are offered up to a whole group of editors who can take their pick. It seems that the next thing that happens is that the manuscript is sent out for peer review. But stop. That’s not correct and it’s really not a good way to proceed. Before sending it out, the designated handling editor needs to read the submission.

Why is reading so important?

The title and abstract really don’t allow a handling editor to decide whether or not a manuscript should go out to review. There are a lot of manuscripts out there that should not have been submitted, because their authors do not have sufficient judgement of their own or because they believe that there is a reason to just ‘chance it’. It is very important that handling editors read the submission, because without that they are moving editorial responsibility from themselves to the peer reviewers.

Some years ago, I co-authored a series of articles (see here) that were published across many journals about how peer review was becoming very difficult for editors because so few colleagues would accept to do reviews. This was a problem then, and it’s still a problem now. I’ve recently sent out manuscripts to more than 15 people before getting two reviews. That peers are not prepared to review, or in many cases even to respond to the request, is very poor. However, more recently I’m experiencing a sharp increase in manuscripts to review that should never have been sent out.

My time is precious, and it’s becoming quite expensive for my employers. I am happy to conduct peer review because it is an important part of the scientific publishing process, and I expect others to review my own work. However, I expect that any manuscript that I receive is worthy of my attention and time. If the handling editor has not read it, they cannot decide this and I really wonder what makes them think that they can send it to me (and presumably others) to read while they don’t feel that they have time to do it themselves. Moreover, this appears to be a trend among younger less experienced editors (often associates) that have either not received any guidance in what their job as editor it, or they should not be editors.

If you are going to be an editor, then you must be prepared to read

I must admit that I’ve done it. I’ve sent out manuscripts to be reviewed as I didn’t have the time to properly read the article, but a superficial skim suggested that it seemed fine. Not good. It’s embarrassing to handle manuscripts that should be rejected without peer review. In the case I’m thinking of, once I’d read through the manuscript later on that day, I realised how bad it was and immediately wrote to those I’d asked to do the reviews and asked them not to. The article was rejected. I only do this if there’s no science contained therein. It’s horrifying how often that’s the case, but I’d rather take on this burden as an editor than burden two or three times as many others to make the same call.

Sometimes, it’s not clear whether or not a manuscript will pass muster. Articles can stand or fall on good or bad single judgements of the authors. But misjudgements aren’t always obvious to editors. That’s why peer review is important, and that’s why it’s hugely important for editors to send manuscripts to appropriate reviewers that have some expertise in a subject. For example, if I receive a manuscript about the calls of East Asian frogs, I shouldn’t only send it to people who work on African frogs. It’s really important that someone familiar with the animals reads the manuscript. This is because they might know something that others would miss. If they spot an error in the identification of the species call in the manuscript, the entire premise of the science might fall apart.

As I’ve discussed before (see blog post here), science is built on the work that others have done before, but basing your work on what someone else has written will mean that you have a good understanding of what they have done and how they have done it. Assumptions have to be made to get anything done, and it’s a good exercise to sit down with a published paper (or even a manuscript or a colleague or your own) and read through listing all the assumptions that are made. Physicists might have a very long list if they read a biologists manuscript, but with some practice you learn to see the assumptions that the authors have made when designing their experiment, or going out to the field to conduct their study. An incorrect assumption could lead to the entire manuscript losing its value.

In my example above, the authors might assume that they had correctly identified the species when recording its call. Such assumptions should be backed up with museum and/or tissue bank accessions. But when they are not, the assumption that the authors are recording what they think they are, is vital. If this is placed in doubt, then the entire premise (description of a call to distinguish this species in the field) simply falls apart. In a case without vouchers, the assumption needs backing up by someone who knows the identification from another study, or without any foundation it becomes worthless.

I’ve been on the other end too

I’ve submitted manuscripts to journals where the editor clearly never read the manuscript. Editors who have made a decision without any guidance of their own gives this away. If your decision comes as a single sentence that asks you to revise according to the reviewers’ comments, then you can be reasonably sure that your editor hasn’t read the manuscript (and possibly not even the reviews).

It’s not surprising that the editors have little to nothing to say; without reading the manuscript, the reviewer comments aren’t really very helpful. Without reading, the editor has no idea whether the reviewer is biased or (as is sometimes the case) deluded. As an editor, you simply have to read. And if you don’t have time to read, you shouldn’t be an editor.

There is worse that goes on in economics

If the above makes some editors in Biological Sciences look bad, then I apologise. Being an editor for a journal is a pretty thankless task and there is no financial gain, and precious little career gain to do an editorial stint. However, if you're going to do it, then you must do it well. The half measures that I describe above are simply not good enough. But biological journals are a huge cut above those in economics. I've always had my doubts about economics as a subject. Rather like theology, it's based on a fanciful construct that puts its own practitioners in positions of power when we'd do just as well to flip a coin.

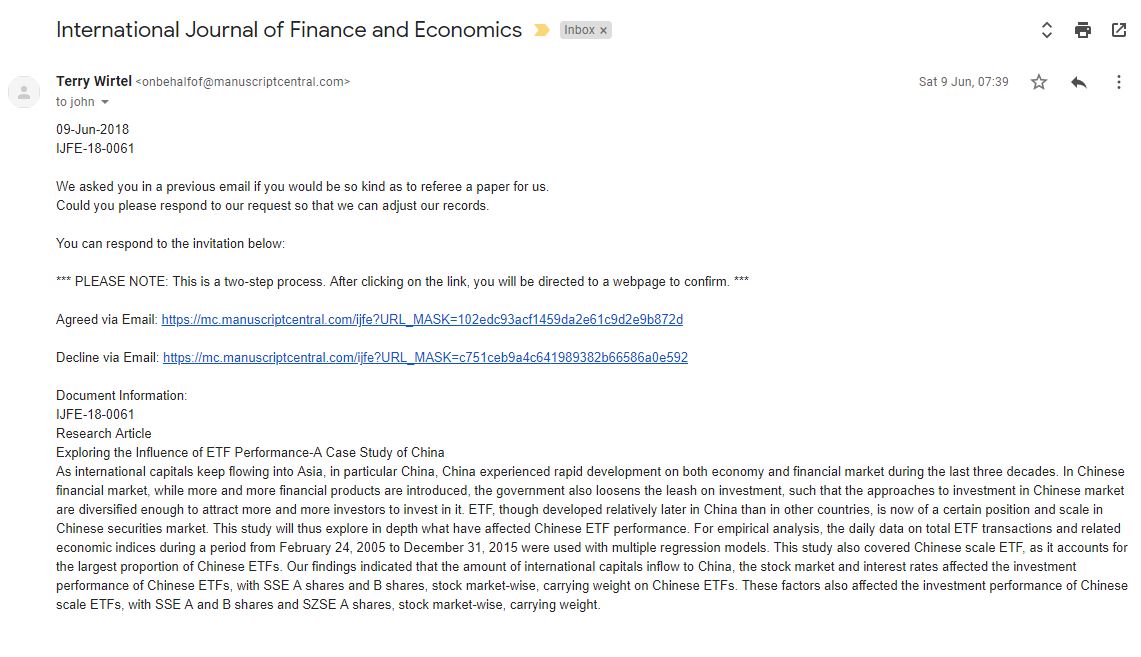

In May this year I was contacted by the "International Journal of Finance and Economics" and asked to review a paper on ETF performance (that's Exchange Traded Funds, but I only knew that now because I looked it up). I deleted the email as I do get a lot of spam from predatory publications, although these usually ask for papers and not reviews. Later in June, I got another email again asking for a review.

I noticed that the journal was published by Wiley, and so I looked them up. It turns out that the International Journal of Finance and Economics is a real academic journal. So why were they asking me for a review on ETF performance? I wrote back:

Hello. Please tell me why you chose me as a reviewer.

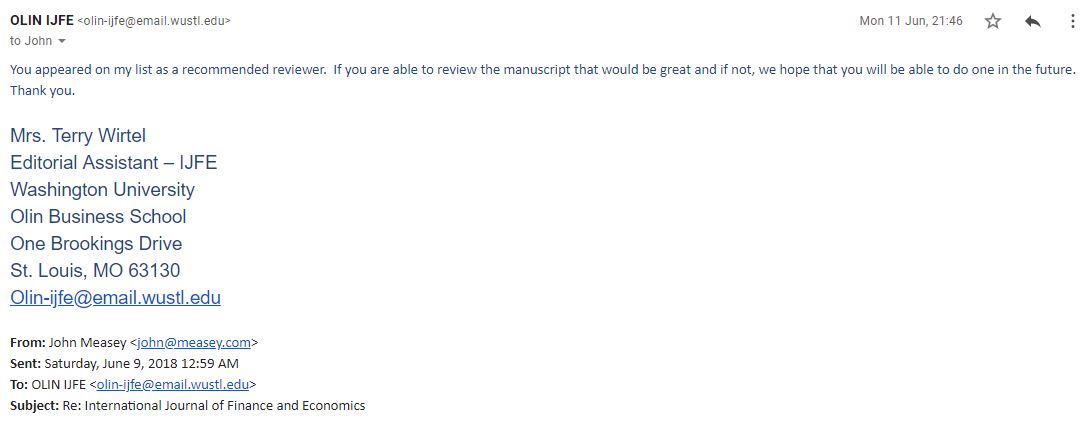

Mrs. Terry Wirtel wrote back with all honesty:

Looking at the website, I note that Mrs. Wirtel is not an Associate Editor, nor an Advisory Editor. It turns out that Mrs. Wirtel is actually the editor’s administrator. I then wrote to the editors Mark P. Taylor (Washington University in St Louis), Michael P. Dooley (University of California at Santa Cruz) and Keith Cuthbertson (Cass Business School) and explained that they should be doing their own editorial work, otherwise their publication is bogus. Perhaps not surprisingly, they didn’t write back.

Although somewhat amusing, this exchange is also a serious worry. When editors, like Mark P. Taylor (Washington University in St Louis), don't do their own work, they leave the reputation of their journal in tatters, and it is reduced to the equivalence of junk status. Interestingly, Mark P. Taylor (Washington University in St Louis) is also the editor of two more economics journals. I'd be surprised if he ever reads the content of any of them.

Summing up

The way to get round making the kind of editorial blunders I describe above is to read the manuscript. The guidance of how to read a manuscript should be explained to editors when they take up the position. There is plenty of information out there on the internet, but the journal’seditorial policy should be understood by all of the editors (and preferably open to authors and reviewers too), and that should include reading manuscripts before sending them out for peer review.

His thesis is entitled: Evaluating the effects of changing global climate on amphibian functional groups of southern Africa: an ecophysiology modelling approach

His thesis is entitled: Evaluating the effects of changing global climate on amphibian functional groups of southern Africa: an ecophysiology modelling approach