What is pseudoreplication?

It is very rare that we can measure every animal in a population, or every measure available in the environment. Instead of such exhaustive sampling, we try to take a representative sample. This sample is something that we can achieve over the period of our study, and which we can use to represent the population or environment of interest. Each data point within the sample should be a replicate, the same measure taken on an equivalent animal. For example, 20 replicate measures of the right hind leg of a frog should involve 20 individuals.

A pseudoreplicate is a problem with the experimental design. Using our example above, if we measured the same leg on the same animal 20 times, we could not claim to have taken a sample of all frog in a population. Similarly, if 20 measures of 20 individuals all came from the same pond, these animals would probably represent the pond well, but not necessarily the entire population (which is presumably made from more than one pond). Thus, pseudoreplication occurs when the measurements taken have a degree of dependence on each other, and therefore aren’t independent.

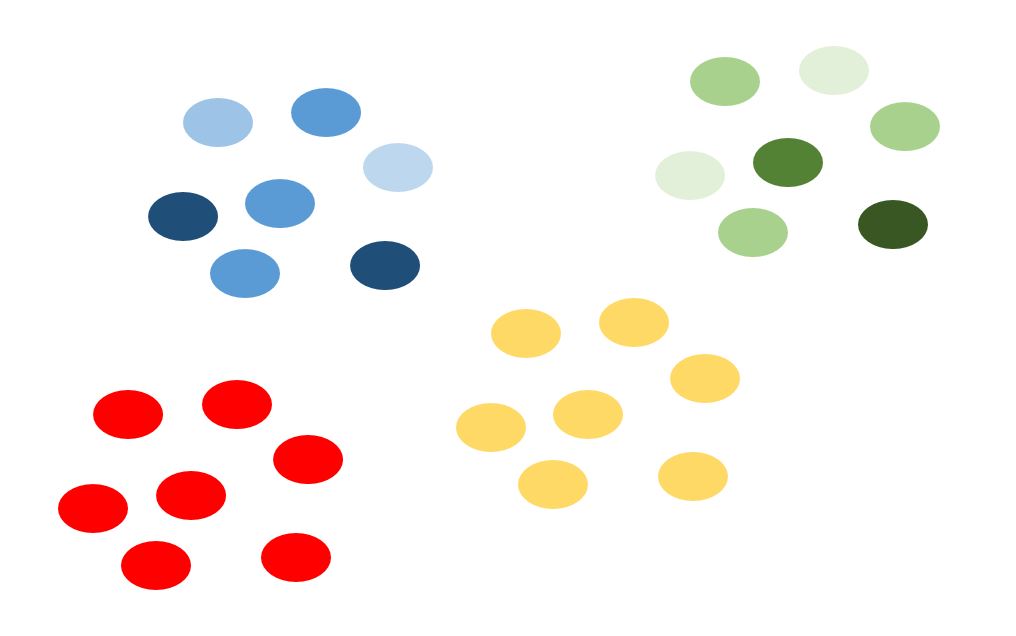

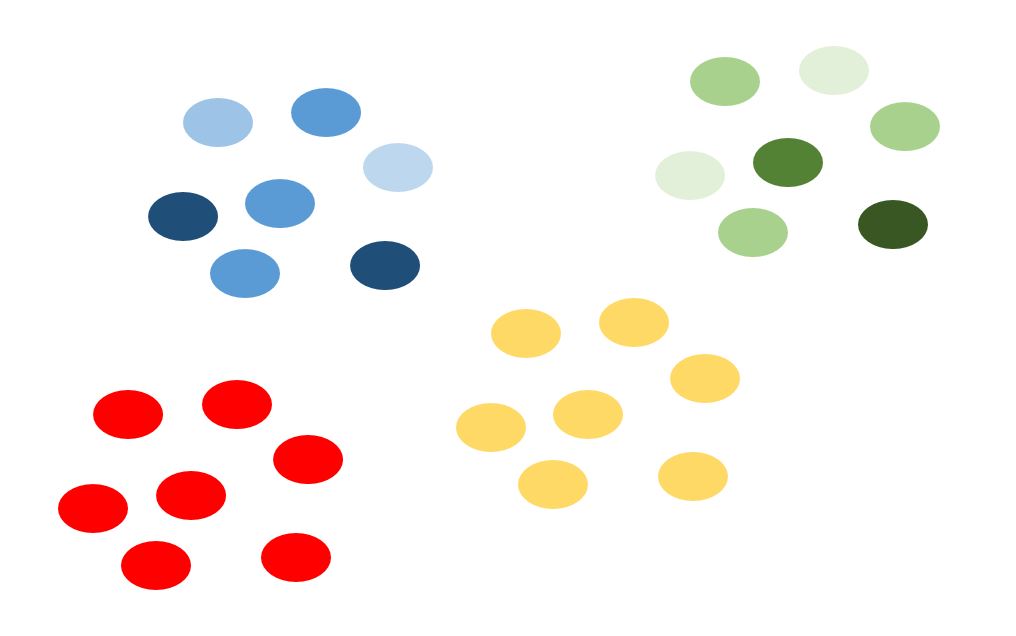

In this image, I’ve used the mean of the length of the frogs’ rear legs to be represented by the intensity of the shading. Taking 20 samples from the blue population would need to involve sampling several of the ponds, similarly for the green population. But in the yellow and red populations, the animals move so frequently between the ponds that all the means are the same. Thus, if you only needed to compare red to yellow populations (for your question), then you only need to sample 20 animals from one of their ponds.

However, this is where the subtlety of pseudoreplication sets in. We may have good reason to believe that the frogs in the pond we’re sampling actually do represent the entire population. We may know that animals in all the ponds in that population regularly move around, and hence measuring 20 animals from any of the ponds is the equivalent to measuring animals from all of the ponds. If the opposite were true, that we believe that the frogs in each pond represent a discrete unit, then we’d have a bigger problem. We’d have to sample evenly across all the ponds in the population to make up our sample, or the alternative would be to take lots of samples from each pond and use the pond as a factor in our analysis. By now you can see that the task is getting more onerous, mostly because the question is becoming more complex. This is a really important point, your experimental design is going to depend entirely on your hypothesis, and (as I’ve stated before – see here) it is really important to know what this is from the start.

If our hypothesis was that the legs of animals in one population were longer from those of another (perhaps because of selective sorting), then we might presume that animals within one pond are closely related (especially at the range edge), and so the ponds would become our smallest repeatable unit. We should then measure only a few animals from each pond, and repeat this for lots of ponds for each population. You can build the ponds into your model when you test you hypothesis, given that you have sufficient statistical power (see here for more on this).

Pseudoreplication in experiments

When it comes to conducting experiments, there tend to be a greater number of points at which you might be pseudoreplicating. A good example is the use of incubators to raise 10 sets of tadpoles from 10 pairs of parents at different temperatures. When each incubator is set at a different temperature (i.e. a different treatment) then this is fine, but if two incubators are used to house 5 of the tadpoles sets each, the largest unit becomes the incubator instead of the parental set of tadpoles. This is because the incubators are unlikely to be able to keep exactly the same conditions (incubators are fickle things). Likewise, this could be a room or some other unit in which you are treating the samples. Imagine that you wanted to extract the gut microbiome of these tadpoles and that you used one kit to extract nearly all of them, but suddenly this became unobtainable and you had to buy another brand to finish off the remaining samples. The kits would become your largest unit, and you’d be falling into the realms of pseudoreplication.

As I’ve emphasised above, pseudoreplication is a problem of experimental design. This is because if you’d designed your experiment properly, you’d know that you’d have ordered the right number of extraction kits, or see that not all your animals are going to fit into a single incubator. When you know about these problems in advance, you’ll be able to make allowances for them by including them as a term in your analysis (essentially testing to make sure that the different kit or extra incubator isn’t an issue - you wouldn’t expect it to be, otherwise it wouldn’t be worth going ahead with the experiment). However, you can’t simply go adding extra terms into your analysis. At some point you’ll run out of statistical power, and you must know that you’re going to have enough before you start. That is, you’ll stand an unacceptably high chance of failing to reject the null hypothesis when it is false (Type II error).

Summary

In summary, pseudoreplication is something that you need to beware of before you start your sampling. A good way of checking if you have a problem with pseudoreplication is to present it to a group (like in a lab meeting), with enough detail in your study design so that they’ll be able to spot it. If you are aware of potential problems in your study, conduct a power analysis to decide how many samples you can take in order to take account of the problem.

Sometimes it might be impossible to avoid pseudoreplication in your study design. If you think it's going to be important, then you'll have to redesign your experiment. If you think it's not important, you'll need to be able to reason intelligently, and be honest about the possibility of pseudoreplication in your write-up (see an example of this here).