The Cape Fold Mountains are the centre of African Clawed Frog genetic diversity

I'm really pleased to see this paper finally emerge. It's a fantastic study that took many years (more than 10!) to assemble all of the tissue samples used. A great many people helped assemble all of these, and the detailed resolution we now have of genetic diversity of this most widely distributed amphibian in southern Africa is excellent.

What did we find?

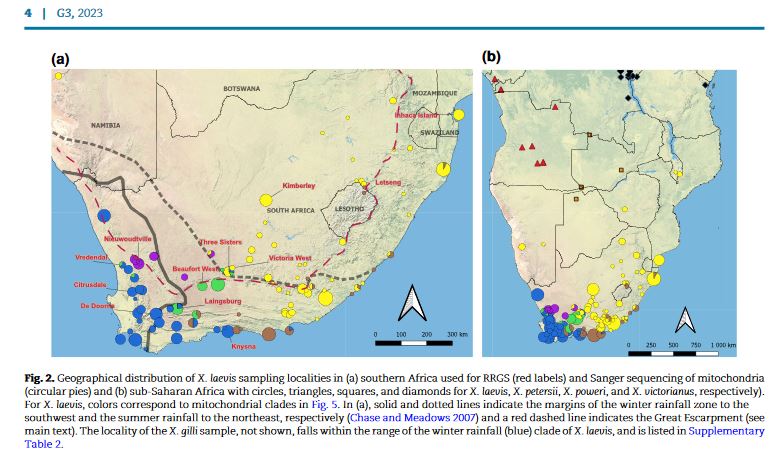

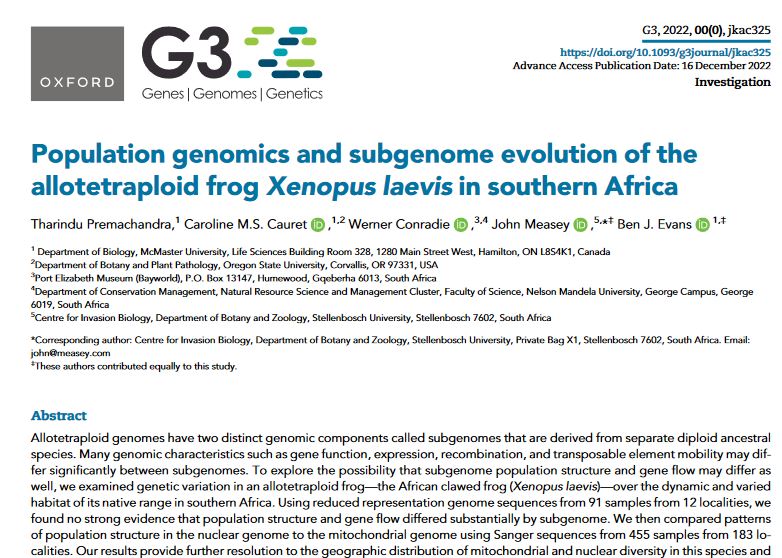

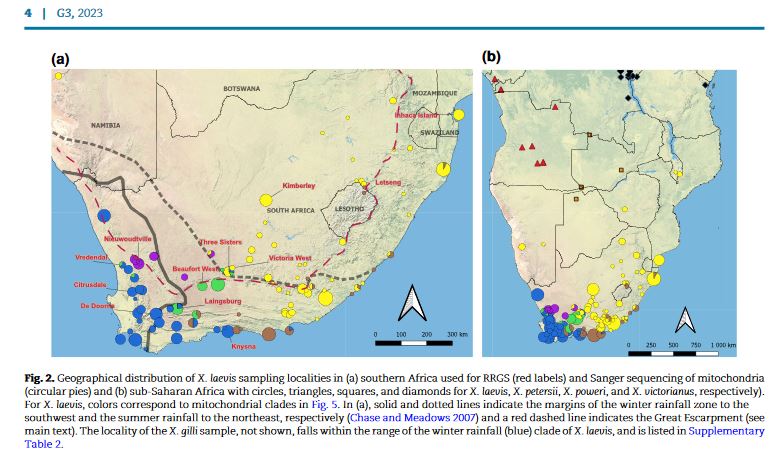

In contrast to previous studies, we found that there are 5 mitochondrial clades of Xenopus laevis in southern Africa. You can see how these are distributed in the following map (Fig 2 below).

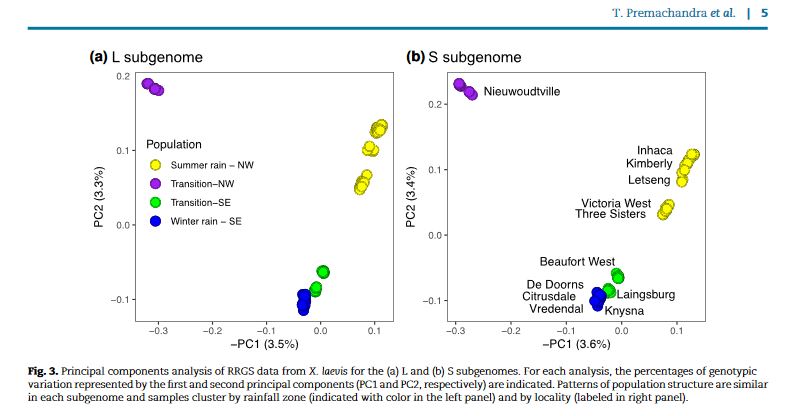

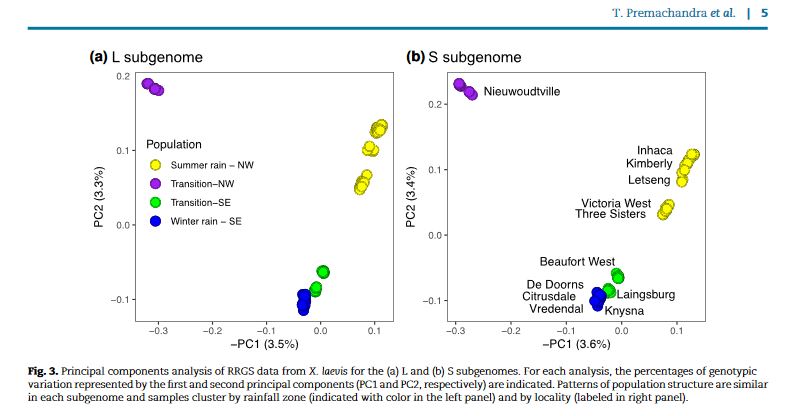

Here you can see (on the right) that most of the area colonised by this species is from a single (yellow) clade. This shows signs of rapid expansion suggesting that even in it's native southern Africa, X. laevis is a very successful species that has recently spread throughout a very large area. The next largest clade (blue) is from the winter rainfall area of the Cape. This includes animals that were sent all over the world for pregnancy testing (Van Sittert & Measey, 2016) and that are currently in the pet trade (Measey, 2017). The Cape Fold Mountains harbour the greatest genetic diversity of this species, and this includes a (green) clade that occurs in the lower Karoo. In the same area is the new (brown) clade, that appears to be co-distributed with the yellow clade up South Africa's east coast. But by far the most different animals in this species come from Nieuwoudtville (purple clade - see Fig 3 below) and adjacent areas of the northwest Karoo. This area is known for having many relict species, but how and why X. laevis became isolated there so long ago is probably related to the large wetland areas that occur along the escarpment. Presumably these remained wet even when lowland areas dried up.

Overall, the picture of the distribution of this species in southern Africa is one of opportunism. These animals readily move into permanent water (e.g. irrigation dams) that is associated with modern farming practices. This has allowed expansion of this species into many arid areas where they might otherwise only appear after unusual rainfall events.

Our data is also the first to examine the entire genome of this model species. In the figure above you can see how the two different subgenomes differ (as X. laevis is a tetraploid species). There is very little difference between the two genomes, suggesting that they are both under selection throughout its range.

This is not the last study on the geographical differences of X. laevis, but it is a great advance from our existing knowledge.

Read More:

Premachandra, T., Cauret, C.M.S., Conradie, W., Measey, J., Evans, B.J. (2022) Population genomics of Xenopus laevis in southern Africa. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics, https://doi.org/10.1093/g3journal/jkac325 pdf

Measey, J. (2017). Where do African clawed frogs come from? An analysis of trade in live Xenopus laevis imported into the USA. Salamandra 53: 398-404. pdf

Van Sittert, L. & Measey, G.J. (2016) Historical perspectives on global exports and research of African clawed frogs (Xenopus laevis). Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 71: 157-166. https://doi.org/10.1080/0035919X.2016.1158747pdf